Asked by the government to provide a frequent a timetable during the Coronavirus outbreak to allow social distancing, TfL have risen to the challenge. But losing £150m a week has pushed the organisation to the brink. We look at their financial options and the possibility that because of their Local Authority status, within 24hrs, they will have no choice but to begin cutting Tube and bus services by law.

Like all large organisations, TfL takes strategic risks seriously. This is something with which any regular reader of their public papers will be familiar. Nowhere is this more true than on the subject of their finances.

This isn’t simply because they are public body (and a relatively diligent one at that). It is also because their unique setup brings with it unique financial challenges and mechanisms through which to approach them. TfL are, in essence, a local authority in their own right. One that employs approximately 28,000 employees directly, and many thousands more indirectly to operate London's vast transport network. Nor does it stop there. TfL are responsible for one of the largest capital (construction) portfolios in Europe - Crossrail, Northern Line Extension (NLE) and more. They aren't just moving London around, in many ways they are helping to build and rebuild it, too.

Their multi-faceted role means that TfL’s finances are always a carefully balanced web of operator income and borrowing. The operational income - both current and projected - supports the borrowing which takes multiple forms - government loans, development funds, the regular paper markets and more. All the time, HM Treasury and the various market ratings agencies (such as Standard & Poor) watch on carefully for fluctuations that would make TfL a bad bet for future loans. Reputation is interest rates and to TfL, interest rates matter.

Coronavirus: A unique challenge

In most major, mid- to long-term crises a transport operator such as TfL might face, the relationship between operating cost and level-of-service required is a direct one.

Take, for example, the 2008 recession. During this period, GDP dropped by 7%, leading to a 2.3% drop in London Underground usage. This represented a significant financial hit for TfL, because the overwhelming majority of its income comes via its 'farebox' - the money passengers pay to be be moved around.

Had the crisis continued to suppress demand for too long though, then this direct relationship between shrinking profits and customer demand would have enabled a difficult, but obvious solution: reduce services to balance the budget.

The challenge offered by a pandemic is different. Indeed it is something that, like many other transport operators around the world, TfL failed to really anticipate. Here, the relationship between falling demand and the service requirement is inverted.

In order to limit the spread of the virus and contain the outbreak quicker, it is important to minimise individual public transport journeys. But it is also critical to run as many bus, Tube and train services as possible. This maximises the spread of passengers over as many separate vehicles and carriages as possible, helping to maintain social distancing.

It is to Mayor Sadiq Khan's, TfL’s and everyone who works in London transport’s credit, that they have been largely successful in delivering the above. Doing so has cost, and continues to cost, lives. As of April 2020, 37 London transport workers were known to have lost their lives to COVID-19, including 28 bus drivers. As this article was being written, another name was added to that list.

The financial impact

Preserving that inverted relationship between services and usage has come at an enormous financial cost. Thanks to the papers published in relation to the emergency TfL Financial Committee today, May 12th, we can finally start to see what that cost is.

TfL are currently running approximately 80% of scheduled bus services and 50% of Tube services. The number of passengers carried, however, has dropped by 85% on buses and 95% on the Tube. This means that it is currently costing TfL £600m a month to operate services.

That leaves an anticipated revenue gap for 2020/21 of roughly £4bn and climbing.

Some mitigating measures (such as the government furlough scheme) and existing emergency funds can be used to offset this, but TfL’s new emergency budget anticipates at least a £3.2bn funding shortfall for this year. This is unsustainable, for a number of reasons, so it is no surprise that TfL are now turning to the government for help.

The myth of more services

Before we look at the issues TfL face in addressing this shortfall, and indeed why this will require financial intervention from the government, we should first address two myths that seem to persist about London (and TfL’s) approach to the current crisis. These are that running more trains is, or would have been easy, and that Londoners can simply use public transport less, temporarily.

That TfL should be capable of running more services was a loud refrain at the beginning of this crisis. It will no doubt manifest again as the government relaxes lockdown and London attempts to return to work.

When uttered genuinely, this myth is the result of the human tendency to translate our lack of knowledge of the complexity of a problem into think it must be simple to solve with 'common sense'.

In the spirit of all complex concepts sounding far better in German, let's call this Abermankönntedocheinfach (“Surely they can just…”).

Abermankönntedocheinfach will always be the bane of transport planners and operators. In London, it manifests particularly strongly when it comes to Tube cooling, ‘driverless’ trains and Tube strikes. In the current pandemic it has manifested in a mistaken belief that increasing service levels is easy.

It is not.

On both buses and trains, more services require drivers and operators who are not sick or self-isolating. There is a finite pool of such individuals, and these are specialist roles. Training new ones is both time-consuming and expensive, even when the entire population of London isn’t ‘staying home’.

Not all of the instances of this myth are genuine, however, and it is important that we call out those that are not. This is particularly true on Social Media or in tabloids.

Some such instances of city-baiting: a chance to show that living in London is ‘worse’ than living elsewhere, while often failing to acknowledge that ‘different’ and ‘worse’ are not actually the same thing. Others are political opportunism and distraction: it is no coincidence that many of demands for more services have come from those, such as the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care Matt Hancock, who have their own awkward questions to answer. Similarly, the prospective Conservative candidate for Mayor, Shaun Bailey, was particularly vocal on a subject that - as a former member of the London Assembly Transport Committee - one might have expected him to display more understanding of.

Finally, many instances of this myth must simply be branded as the incidents of hate they are. They are overt or dog-whistle attacks targeted at London’s minorities, in an effort to portray them as somehow ‘un-British’, or at Mayor Khan himself, because of his ethnicity or religion.

There is no need to debate this myth when it is raised this way. Doing so only serves to amplify those who do not deserve to be amplified.

The myth of reducing public transport usage

The second myth that must be addressed is that demand for public transport usage in London can be reduced, even temporarily.

The scale of executing this challenge in London is something that is understandably difficult to grasp outside of the capital, or indeed outside of the UK. Nothing highlights this better than the updated advice issued by the government this week on public transport usage across England. This recommends that public transport should be avoided, where possible, while restrictions on car journeys are eased.

“Drive to work” may sound like a reasonable temporary measure. And indeed for the majority of the UK it is not only reasonable, but a return to the norm. In London, however, this simply isn’t possible.

This is a complex issue, and one which could easily translate into an article in itself. A few very broad comparisons, however, should serve to highlight the difference between London and the rest of England in this area.

The population of Greater London, for example, is approximately 8.6m. The rest of England equates to approximately 47.4m. In 2011, the DfT published driver licence data split between London and ‘rest of UK’. Adjusted for ‘England only,’ this highlights that roughly 50% of people in England, excluding London, hold a driving licence. In London, this figure is only 25%. Again, this is a broad comparison, but the difference is marked.

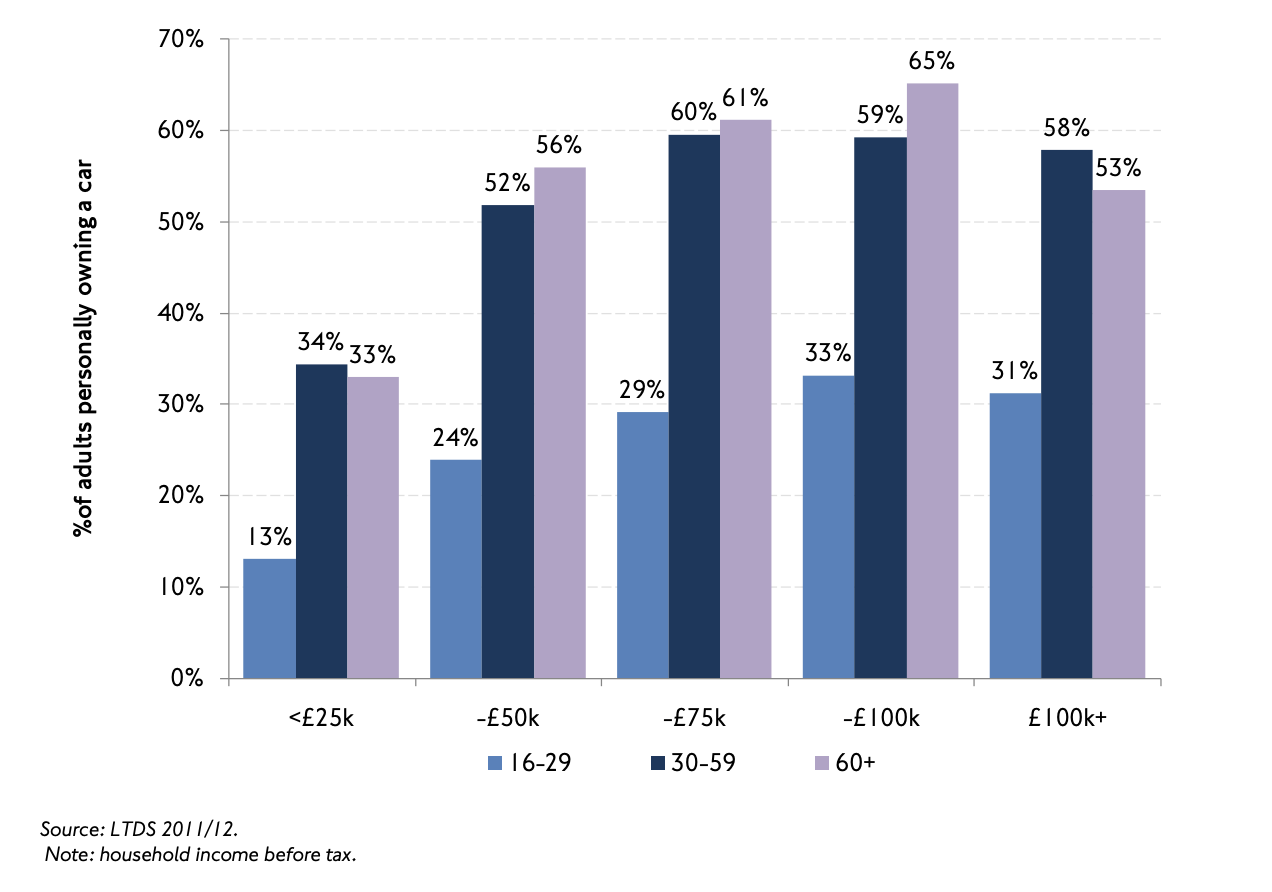

Even when London households do have access to a car, the balance of that access is different to the rest of the UK population. TfL have some good statistics on car ownership and access, and we have included some graphs below.

All the data demonstrates a key issue for getting London back to work without using public transport: If you are young. If you are low-income. If you are female. If you are from a minority ethnic group. If you are any of these things or more, then you are less likely to have access to a car right now than even other Londoners, who we we have already highlighted are significantly less likely to own a car than elsewhere in the UK. And there is a better than average chance that you would not know how to drive it anyway.

Using public transport in London is not optional. It is a necessity.

Solving the funding gap

Understanding the unavoidable role public transport plays in London is important, because it highlights what isn’t a solution to TfL’s operational funding crisis: reducing services in any significant way. If anything, services are going to need to increase in the coming weeks as demand starts to trickle up again, rather than the other way around.

This leaves two major options: some form of financial relief package from the government, or increased borrowing from either public or private sources. It is worth looking at TfL’s borrowing options first, as these are more constrained at the moment than TfL themselves are generally prepared to admit.

TfL have a long history of borrowing, primarily for capital investment (e.g. Crossrail or rolling stock purchases) but also to meet operational need, as outgoings naturally don’t always align with the incoming revenue curve (similar to how football clubs borrow against season ticket sales).

That borrowing has always taken multiple forms, all strictly governed by the various legal acts under which TfL operate. These place limits on things like its overall debt ceiling and even what currencies they can actually borrow in (Sterling, unsurprisingly, by HM Treasury decree).

Let's look at some actual figures. Last year, TfL borrowed approximately £640m from the market in some way. This was actually slightly down on their forecast borrowing for the year (£730m) and excludes a separate line of borrowing worth £750m, set up with the DfT. This was specifically ring fenced for meeting the Crossrail project overrun costs. Overall, this brought TfL’s total current borrowing to approximately £11.5bn. For context, this is roughly twice TfL’s annual income of about £5.8bn.

What matters less than understanding the minutiae of those numbers is noting the relationship between them. In proportion to its income, TfL are carrying a lot of debt already.

All of this is within their borrowing limit, but hasn’t left much room spare. Indeed one thing they have had to become increasingly conscious of is their rating with agencies such as Standard & Poor. These act like a credit rating for organisations and - just as with personal debt - an agency rating affects the interest you are likely to be charged (or need to offer) on your debts and bonds.

Indeed to address potential concerns about the amount of debt they were already carrying, TfL agreed to start maintaining a funding reserve of £1.2bn at all times, on top of existing operational reserves, for potential loan-related payments. Again, this isn’t unusual - Arsenal Football Club did something similar to reduce risk and interest on the large loans they required for the Emirates Stadium - but it helps highlight once again that TfL is already running close to the limit of what it can effectively borrow.

Now to the current situation. Of the £4bn shortfall TfL are forecasting, they estimate that they can absorb about £800m via strategic reserves and other means. That already leaves another £3.2bn of outgoings to cover, and adding that much debt to their existing pile is, quite simply, not an option.

To use a domestic metaphor, TfL are already paying off a mortgage, have maxed out two credit cards, and are half way through the balance on a third. Now they suddenly find themselves needing to pay for a new roof, and they don't have enough credit left on that last card.

Scoring points

It would be easy to point fingers and ask just why TfL are so heavily extended. No doubt we will see such comments in the coming months from those either unfamiliar with the way transport funding works, or simply looking to score points. The question of Mayor Khan's ill-judged Fare Freeze will no doubt be raised again. As we pointed out when the manifesto pledge was made, this was a mistake. In doing so, he surrendered one of the few mechanisms the Mayor has to tweak TfL's farebox year-on-year.

What has become clear over time is that this decision was made, in part, because Khan's team had indulged in an ill-judged piece of Abermankönntedocheinfach of their own. They'd seen fare increases as linear - that is, that they yield the same increase in revenue year on year - and believed they could easily budget for that. But this isn't how fare rises work. They scale in multiples.

There is no doubt that this decision has cost TfL upwards of £650m in cumulative revenue in his first term. Khan and TfL point to savings made elsewhere to counter this, as well as claiming that it has offset what would otherwise have been a fall in passenger numbers due to decreased cost of travel.

On this, we remain unconvinced. What is true, however is that the Fare Freeze has no real impact on the unprecedented situation today. TfL do not have £12bn of debt because Sadiq Khan decided to forego £650m of farebox revenue over the last four years. Claiming otherwise is the kind of basic mathematical failure that would make a Year 3 schoolchild blush.

In a similar vein, the government easily cannot reasonably point at TfL and say that it is their own fault that their existing borrowing is so high.

It is true that recently much of it has related to Crossrail overruns, for which TfL must ultimately take the blame. Despite their occasional protestations to the contrary, the buck stops with them and the Mayor. That they were forced to borrow to deal with those overruns, however, was something on which the last Conservative government insisted.

On top of this, a considerable amount of TfL’s legacy debt has been incurred dealing with the ruthless cuts in funding that happened under the 'Austerity' Conservative governments of David Cameron, or on projects directly pushed by Boris Johnson as Conservative Mayor for London. This includes the Garden Bridge, as well as the cancelled Metropolitan Line Extension to Watford, to focus on just a few big-ticket items.

When is a bailout not a bailout?

All of these factors mean it will be hard, if not impossible, for the government simply to dismiss TfL’s current issues by demanding that they take on more debt. Drawing too much attention to why TfL’s debt exists is likely to raise awkward questions about previous Conservative governments, and the former Conservative London Mayor in charge of the current one.

Indeed the TfL committee papers indicate that ‘constructive’ funding discussions with the government are currently underway. These will no doubt be happening with some urgency, as TfL will already be approaching the limits of their contingency funding for operations in a crisis (as a responsible operator, TfL have always kept a 60 day operational reserve in place for exactly this scenario).

Those constructive talks are likely focused on a way to take some of TfL’s existing debt off of it, in a way that doesn’t scare the Treasury or the DfT. Perhaps more importantly for the government, it will need to be in a way that isn’t seen outside the M25 as a ‘cash payment’ to London. This is, of course, the downside of the current political model of never thinking more than one Daily Mail headline ahead. Poking the biggest sub-economy in the UK and its transport network may earn you fawning headlines on a regular basis when times are good, but backtracking from that then becomes somewhat problematic in a genuine crisis.

The need for London’s economy to rebound, however, may provide the clue to the likely solution. This lies in the sheer economic impact of TfL’s current capital investment programme - Crossrail, the NLE, new trains and rest. Those projects have an enormous economic impact not just on London, but the UK beyond. As the committee report points out:

“The majority of our costs are spent on our supply chain and internal labour costs: in the financial year 2019/20, we spent around £6bn through our suppliers. Without a stable source of income or funding during the COVID-19 pandemic our supply chain will not be able to gain adequate assurance that TfL will be able to fund their future commitments.”

TfL Finance Committee Paper, May 2020

One can read that paragraph as either a hint to the direction of current discussions, or as a threat to what will happen should they prove unsuccessful. There is £6bn of downstream work reliant on TfL finding a way out of their current crisis. Much of that work is in areas such as construction and manufacture that the government is not only keen to see resumed, but resumed in a responsible way. TfL are likely pointing out that, with the controls they are in a position to put in place over their various projects, they are capable of being an excellent example of ‘Stay Alert’ done properly. Or they are, if they can feel secure in their operational funding.

The betting money here at LR Towers, therefore, is on a funding package that looks to lift some of the existing debt accrued on projects such as Crossrail off of TfL's books, which can be packaged up as economic stimulus. This would then allow them to largely borrow their way through their operational funding issues, through regular mechanisms.

This would leave TfL no worse off than they are now, but make it very clear, from a government perspective, that this is about kickstarting the UK economy in an orderly fashion and preserving service levels, not giving a ‘financial boost’ to the capital. Which wouldn't play well with either the Shires or the newly blue elements of the north.

Coupling any such debt relief with a pause on new capital projects (such as the Bakerloo line extension or Crossrail 2) and a temporary review process for future projects with heavy DfT involvement would also allow the government to save face. Such measures would also make reasonable sense anyway. Just what shape travel demand, and funding availability, will be in London once the pandemic passes is anyone’s guess. Not reviewing such projects would be bad policy all round.

On a political level, a new review mechanism would also give the Conservative government, as well as those within the DfT who may feel that TfL have flown a bit too close to the sun in recent years, an opportunity to publicly clip both a Labour Mayor’s and his transport fiefdom’s wings.

Whether that is deserved or not is open to question, but this is an area where the latter two have hardly helped themselves in recent years. On the subject of both rail devolution and (when things were going well) Crossrail, Khan and TfL were both happy to publicly poke central government. What goes around, comes around - something that they may pragmatically have to accept in the quest for a reasonable solution.

Remember that bit about being a Local Authority? It matters

Whilst the signs are thus positive that some kind of funding arrangement will be put in place to see TfL through this crisis, both TfL and Londoners should be wary that the risk of an alternate approach still remains.

That approach would be for central government to abdicate its responsibilities to help and place them on London instead. It would be to lean into that flawed principle of Abermankönntedocheinfach and claim that TfL ‘can surely just…’ find some money somewhere else, or even just keep kicking the hard decision on funding down the road until TfL’s reserves run out and it is too late to deal with this financial crisis in a sensible way.

This would perhaps be a more disruptive route to take than some in government might currently realise. This is because of something that we mentioned at the beginning of this article. TfL is, to all intents and purposes, a Local Authority.

This brings with it some statutory requirements.

One of those requirements is that it runs a balanced budget, in line with its previously agreed budget. If it cannot do this - or more importantly if its CFO believes that it cannot do this - then certain processes automatically come into play.

This includes the issuance of a Section 114 notice. A Section 114 notice indicates that the Local Authority cannot meet its financial obligations for the year, and it must not engage in any new activity that might further aggravate the current financial situation, beyond delivering its minimum statutory obligations and - within 28 days - convene a board meeting to agree to a new budget that would bring it under budget.

This isn't a catastrophe. If anything, it is a process meant to protect core local authority services in times of crisis. The problem for TfL, however, is that a close read of the GLA act will reveal that its statutory obligations are way more limited than one might expect. Largely because this is one of those situations that no-one ever really thought would occur, so people assumed a lot of things weren't necessarily important to spell out in the Act.

What does that mean today? Well, to quote TfL's Chief Financial Officer, Simon Kilonback:

I think it will shock everybody, if you are to read the GLA Act, just what our minimum statutory obligations are as a transport authority. It does not include running a Tube service. It includes running a minimal bus service for children living more than two miles away from their school. It requires us to run the Woolwich Ferry, and it requires us to regulate and license the taxi and private hire trade, and it has some obligations on highways maintenance. But it does not include a minimum obligation for the running of our core transport services.

So it is inevitable, if we are unable to agree the funding in short order, that we would have to take steps to reduce our core costs, by reducing the amount of services that we provide to London.

Simon Kilonback, CFO TfL, Finance Committee, May 12th 2020

It should be emphasised that this doesn't mean that the Tube will stop overnight. TfL can continue doing anything they're already doing, within reason. But it does mean that if they have to budget for cuts, then - in accordance with the Section 114 - many of the services that will be hit will not be those that TfL's critics probably see as 'waste'. It will be core services on which London relies. At the very least, extending services and carrying out a whole range of other activities necessary to facilitate a return-to-work for London will necessarily be curtailed while the mess produced by the initiation of the Section 114 process are unpicked.

It is worth noting that, as of May 12th 2020, Simon Kilonback has indicated to the TfL Finance Committee that without the conclusion of a deal with the government within the next 24 - 48hrs, he will have no choice but to begin the Section 114 process for TfL. To quote:

I think if we are unable to conclude the financial negotiations within the next 24 - 48hrs, then we will have to... I think it is unavoidable at that point that we will have to commence the statutory Section 114 process.

Simon Kilonback, CFO TfL, Finance Committee, May 12th 2020

The FINAL risk remains

Beyond all of this, there is still one further option the government could take. It perhaps represents the 'absolute worst case' scenario. That is to simply claim that Londoners ‘can surely just’ follow the same guidelines as everyone else. That all that is required to deal with this crisis is ‘common sense’, or ‘British determination’, or any other phrase that uses inverted commas as protection from critical scrutiny. Weak leaders, of all political persuasions and managerial levels, like phrases like this because they allow them to appear to offer a solution whilst failing actually to do so. They are a way of encouraging people to generalise their own experience into a collective one, and in doing so abdicate both responsibility and blame for the inevitable problems or inequalities that then occur.

Public transport in London is not optional or avoidable. It is both a necessary and inevitable part of the solution to the COVID-19 pandemic. The Mayor, TfL and every single person working in London transport right now are doing their part to keep London moving, at enormous personal, human and financial cost. It is time for the government to step forward and help that vital effort continue.

Like what you have read? LR is community funded! You can back us on Patreon here. Every little helps...