Despite impressive advances, bus battery technology is still not optimal – poor range, and reduced energy storage in cold weather. So to avoid putting all their clean energy buses in one basket, TfL has consistently been evaluating hydrogen fuel cell buses.

Long before the first official determination of pollution as the cause of death of a 9 year old London girl shone the spotlight on the impact of pollution on respiratory systems, London had been at the vanguard of advancing clean transport technologies.

Additionally, a recent series of troubling London air pollution reports, such as the levels of nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and other toxic volatile organic chemicals (VOC), are shedding new light on the extent of inhaled toxins and carcinogens on the Capital's streets. Diesel bus exhaust results in buildup of NOx (NO + NO2) inside bus terminals.

The sudden reduction of cars, trucks, and buses in March 2020 due to the onset of the pandemic just as quickly resulted in clear skies over major cities worldwide. Unfortunately, traffic quickly returned, and the startling view of crystal clear air that shouldn’t be easily forgotten, has been forgotten. We note the recent realisation of the impact of brake and tyre particulates on air quality and breathing, but address only zero emission buses in this article.

TFL's Zero emission buses

To tackle the capital’s air quality crisis believed to be largely caused by diesel engines, recent Mayors and TfL had initiated a number of new clean air transport initiatives. We recently covered battery buses and ULEZ's in On The Buses: Fares, Fumes and Finances, and now look at the role that hydrogen fuel cell (HFC) buses are starting to play.

We had first looked at London’s hydrogen buses in 2014 in Asphalt and Battery: The future of the London Bus (Part 2):

When you are responsible for a fleet of over eight thousand diesel buses it is only right and proper that you investigate alternative options and this TfL has done. At one stage hydrogen looked very promising. In the past few years TfL have experimented off and on with hydrogen buses on route RV1 but, whilst the latest buses are still in service, there does not seem to have been any effort made to extend them beyond this one route. This is probably because they are very expensive indeed. It is also the case that, although hydrogen can be seen as a solution for getting rid of tailpipe emission at the point of use, it does not solve any energy issues because more energy in the form of electricity is required to extract the hydrogen from water than can be obtained from burning it as a fuel (and creating water). As such, hydrogen is merely an alternative to the battery.

There are of course various other gases apart from hydrogen that can be burned. The problem with these are that they are still hydrocarbons but in gaseous rather than liquid form. The main attraction of these fuels for taxis and other vehicles is that they don’t attract fuel duty – something that bus operators don’t pay anyway.

Transport in London has had a long history of innovation, from the pioneering Metropolitan Line in 1863, the first electrically powered Underground line in 1890, to the world's first automated underground line in 1968. Buses have not been exempt from technological advancement, with London at the forefront of bus technologies and designs such as the original Routemaster.

London’s first hydrogen bus route - RV1

TfL’s first foray into hydrogen power started on Riverside bus route RV1 in 2002. The route connected Central London with South Bank attractions, including the Royal Festival Hall, National Theatre, London Eye, and Tate Modern, and operated between Covent Garden via Tower Gateway station, Waterloo, London Bridge station and Tower Bridge, serving many streets that previously had not been served by buses. The short 6 mile route length, dense central London routing and high visibility to tourists meant that RV1 was an ideal route to trial and fly the environmentally friendly bus flag - the only emissions of hydrogen vehicles being oxygen and water.

The hydrogen buses serving on this route were initially three hydrogen fuel cell (HFC) powered Mercedes-Benz Citaros operated between 2004 and 2010. Some of these buses were also trialled on route 25 in 2009. This small fleet allowed TfL to compare their efficiency directly against diesel powered Citaros. However, due to a lack of hydrogen capacity in those buses, their limited range only allowed operation in the mornings and early afternoon. Whilst the RV route prefix was part of Riverside branding, there was cynical speculation that it also meant Research Vehicle.

The Citaros were removed from RV1 service in 2010, replaced by eight new Wrightbus Pulsar 2 hydrogen-powered VDL SB200 bodied single-decker buses purchased by First London, which were operated on the route until 2013. Two Van Hool single decker hydrogen fuel cell A330FCs replaced the Alexander Dennis Enviro 200 Darts on route RV1 in January 2018, allowing a full hydrogen fleet to operate for the first time.

Some of the RV1 hydrogen buses have apparently had poor ride quality and high interior noise levels, equivalent to a diesel bus. As a comparison, battery electric buses are considered far superior in these respects.

Massive cutback in RV1 bus frequency after London Bridge rebuild

Part of route RV1's continued raison d'être was the Thameslink Programme London Bridge rebuild. The biggest capacity gap it was helping to fill started to fall off post May 2016 (when the bus route ridership halved), then in August 2017 with the station works phasing changes. With the Blackfriars Southern entrance opening, combined with renewed peak Thameslink service from London Bridge, the 2019 RV1 ridership dropped to about 10% of what it once was.

It was thus no surprise that route RV1 was discontinued on 15 June 2019. Diesel bus route 343 was then extended from Aldgate to Tower Gateway to replace the service between London Bridge and Tower Gateway. The Wrightbus hydrogen single deckers were moved to route 444 and the Van Hools to storage.

To develop a dedicated hydrogen source, TfL are coordinating with Project Cavendish, a collaborative feasibility project between Southern Gas Networks (SGN), National Grid, and Cadent. This project is evaluating the potential of using the Isle of Grain’s existing infrastructure to supply hydrogen to London & the South East, including hydrogen generation by steam methane reforming (SMR), storage, and transport. Sixty kilometres east of London, the Isle of Grain hosts the National Grid’s Grain liquid natural gas (LNG) terminal, as well as a number of gas shipping terminals, gas blending facilities, and considerable natural gas storage.

SMR is the traditional hydrogen generation technology, also called ‘gray hydrogen’ for its dirty fossil fuel production method, which releases carbon into the atmosphere during processing. However, this process can be rectified with CO₂ capture, to a low-carbon standard to make ‘blue hydrogen’. This is the hydrogen that TfL is hoping to use.

Next Generation hydrogen buses

In 2018 London once again took a technological jump on transport innovation - TfL commissioned two hydrogen fuel cell double deckers – a world first. One is a conversion of a former hybrid bus demonstration vehicle, and the second is a brand new double decker Streetdeck FCEV (fuel cell electric vehicle), again from Wrightbus, powered by Ballard hydrogen fuel cells. They are due to be trialled by Tower Transit from Lea Interchange garage.

The Mayor’s imperative

Mayor Sadiq Khan has made tackling the public health issues caused by air pollution one of his major initiatives. Toxic air is a threat to all Londoners’ health, especially children, the elderly, and those with lung and heart problems. Scientific studies are starting to show that high values of air pollutants correlate with more severe COVID symptoms.

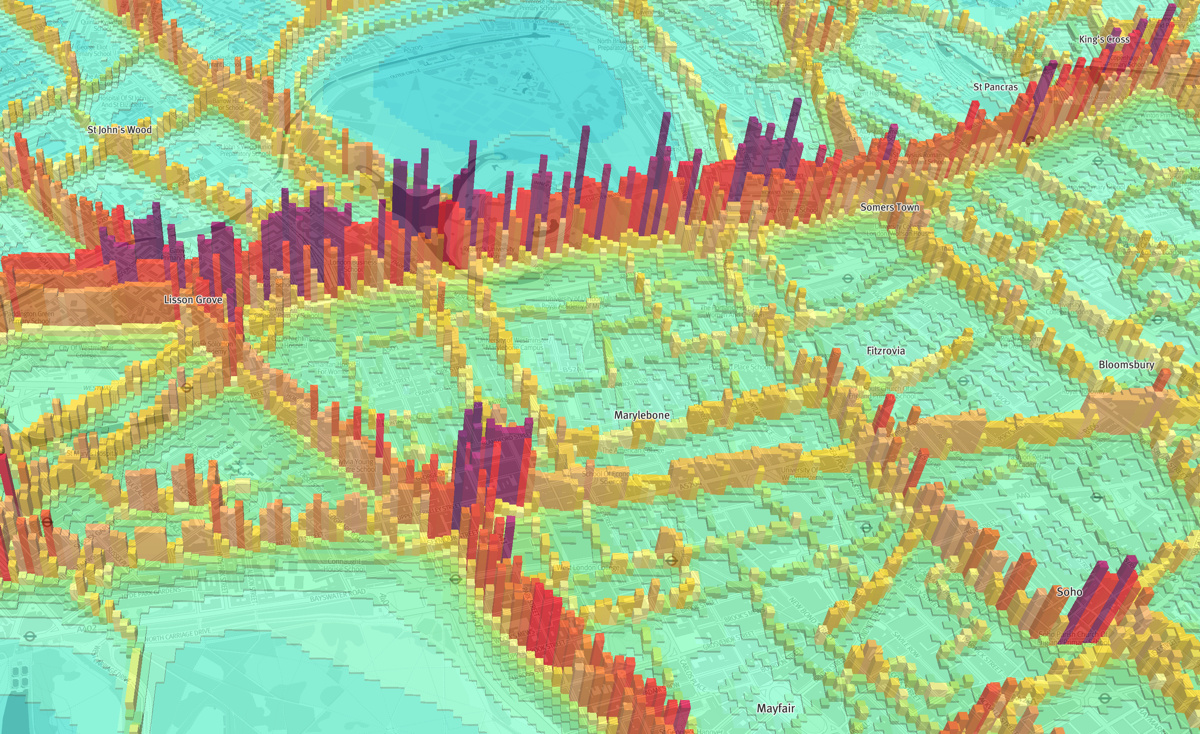

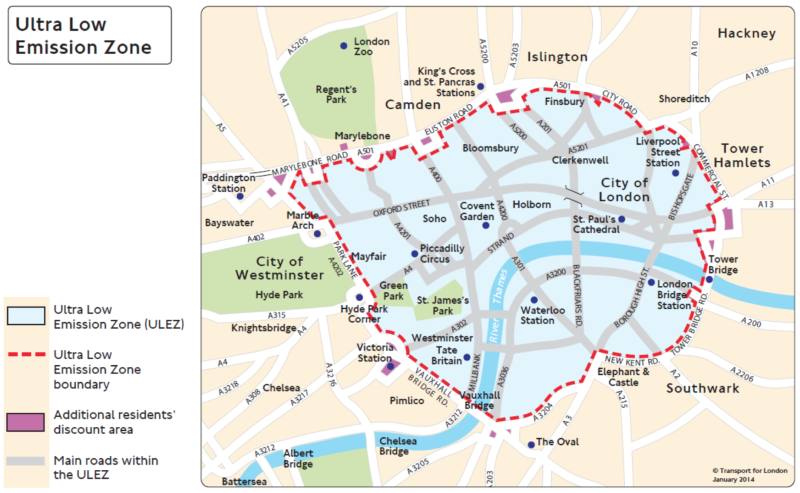

Under his initiative, the 2019 Mayoral Plan set the goal of 2,000 zero-emission London buses by 2025, and a full zero-emission bus fleet by 2037 at the latest. When TfL introduced the ten Low Emission Bus Zones and the world's first Ultra Low Emission Zone (ULEZ) in April 2019, harmful nitrous oxides (NOx) emissions were reduced by 90% on some of the capital's busiest roads in only a few months.

TfL then announced in May 2019 that it will introduce 20 of the new Wrightbus hydrogen buses into service in 2020 on London bus routes 245, 7 and N7. All of the buses in the ULEZ, and 75% of the entire bus fleet, already meet these standards. The plan was to have the entire TfL bus fleet meet the standards by October 2020, making the entire city a Low Emission Bus Zone. Unfortunately, one of responses to the coronavirus pandemic was to temporarily remove the ULEZ restrictions.

TfL's currently operates over 200 zero emission buses, Europe’s largest electric fleet, mostly battery powered. However, hydrogen buses can store more energy on board than equivalent battery buses, meaning they can be deployed on longer routes. Hydrogen buses now only need be refuelled for five minutes once a day, making them much quicker to refuel than to recharge battery buses.

In June 2020 Ryse, a hydrogen generation company, and Wrightbus, the manufacturer of London’s New Routemasters, won the 10-year contract to deliver these buses in 2020. Once the new Wrightbus hydrogen bus squadron is in service, London will have the largest zero-emission bus fleet in Europe. We know what you're thinking - so hold that thought.

Billionaire invests in hydrogen

Ryse Hydrogen is owned by Jo Bamford, the son of billionaire and JCB construction firm owner Lord Bamford. The alternative fuel company plans to power thousands of hydrogen buses, as other British cities are also trialling hydrogen buses – such as Liverpool, which is placing ADL fuel cell double decker buses into operation. In 2016 a hydrogen bus cost more than £1m, but in 2019 it is only £350,000. A comparable diesel version costs roughly £230,000. Bamford fils believes that this drop in hydrogen bus prices now make hydrogen generation a growth market. As seeming confirmation of this, Ryse was recently awarded a contract to provide hydrogen powered buses to Aberdeen under similar European Union funding.

Roadblock to hydrogen - it's financial not technical

Unfortunately, there was a sudden major roadblock to TfL's plans - Wrightbus slid into insolvency in late September 2019. A saviour was feverishly sought for one of Britain's few remaining bus manufacturers, as we covered here.

The billionaire doubles down his bet

But at the last minute, it was Jo Bamford who took over Wrightbus, via Ryse Hydrogen on 11 October 2019. Now under the new Bamford Bus Company, the new owner has restarted production.

Other funding sources

Trialling such new transport technology is not cheap. TfL is investing £12m in the 20 new Wrightbus hydrogen buses and fuelling infrastructure. More than £6 million of the funding for this is being provided by the Fuel Cells and Hydrogen Joint Undertaking (FCH JU), the Innovation and Networks Executive Agency (INEA) of the European Commission, and £1m from the UK Office of Low Emission Vehicles. Note this means that the net capital cost to TfL is £5m for these 20 new buses – plus some extra operational costs – which prices the new buses at a comparable level to conventional diesel buses, for these initial examples. What a production line bus might cost TfL or lessors, could be a different matter.

JIVE talking

TfL hopes to acquire up to 150 hydrogen powered vehicles. Interestingly, TfL is leading the procurement on behalf of a number of UK transport authorities and bus companies, rather than just for London. The specific aim of the procurement is to generate interest from a range of potential suppliers so as to offer a choice of technological solutions and innovation and, obviously, to create price competition for the supply of such buses. It is also worth noting that the latest Green Bus funding awarded by the government provided a contribution for the supply of 42 hydrogen vehicles - with London and Birmingham named as recipients of this funding. TfL is also a lead partner in the Joint Initiative for hydrogen Vehicles across Europe (JIVE) project, to encourage the implementation of this clean technology in other UK and European cities. JIVE aims to bring down the unit vehicle cost by volume buying with other authorities.

H2Bus Consortium

Concurrently, a new group of companies called the H2Bus Consortium also formed and is working to deploy 1,000 zero-emission fuel cell electric buses (FCEBs) and supporting infrastructure in European cities, including London, by 2023. The high upfront cost of the buses and refuelling infrastructure is the main barrier to the adoption of fuel cell buses. So H2Bus has the goal of providing a single-decker hydrogen bus price below €375,000 and bus servicing of €0.30 per kilometer. This would make the scheme cost competitive with diesel and hybrid buses. Consortium members are Ballard Power Systems, which designs and manufactures hydrogen fuel cells, Everfuel, Wrightbus, Hexagon Composites, Nel Hydrogen, and Ryse Hydrogen.

An initial 600 FCEBs are being supported by a €40 million grant from the EU’s Connecting European Facilities (CEF) program, with 200 to be deployed in each of Denmark, Latvia, and the UK by 2023.

The Ballad of Ballard Power

Hydrogen fuel cells for buses have had a long development gestation period. In 1998, Ballard Power Systems of Vancouver, Canada was a technology darling stock. It had won orders for a number of hydrogen fuel cell (HFC) demonstrator buses, which promised clean electric power with pure water being the only waste product. But few companies better demonstrate the Hype Cycle for Emerging Technologies than Ballard:

Whilst Gartner did not rate HFCs in the late 1990s, here's how the Ballad of Ballard played out. The wave of initial optimism placed the company at the Peak of Inflated Expectations. But the company quickly hit financial and physics reality, and plummeted into the Trough of Disillusionment in the early Naughts. Rumours of one of Vancouver’s Ballard HFC buses allegedly catching fire did not help.

Little was heard of Ballard for years after, but the company was quietly trudging up the Slope of Enlightenment by diligently refining its fuel cell technology. Ballard HFCs are currently powering over 100 buses worldwide, with another 500 under construction. In the UK, Ballard powered buses have amassed over 30,000 hours of fuel cell operation in London.

Hydrogen - there's the rub

The biggest fallacy about hydrogen is to think of it as a fuel source. It needs to be created first. The principal drawback is the that it takes thrice the energy to produce hydrogen by electrolysis, the cleanest method, than the hydrogen will embody.

A case of sustainable hydrogen generation is found on the windy Orkney Islands, which have many wind turbines. Despite the popularity of electric vehicles on the island, there is nearly always excess electricity. They can't send much of it to the mainland because of inadequate interconnector capacity. So they generate hydrogen which is used to power the ferry to the mainland.

Unfortunately, to date excess wind power only produces a limited amount of hydrogen worldwide.

The economic reality of hydrogen

- The main aspect holding back widespread hydrogen fuel cell adoption is the cost of generating hydrogen and developing the hydrogen distribution network.

- A report by the German Association for Electrical, Electronic & Information Technologies (VDE) electrical standards and research group was undertaken to compare the cost-effectiveness of battery electric multiple units (BEMU) and hydrogen electric multiple units (HEMU). The study determined that BEMUs are currently 35% cheaper to acquire and operate than hydrogen fuel cell equivalent trains (hydrail).

The study assumed that only ‘green hydrogen’ produced from renewable electricity sources will be used. However, in practice much cheaper ‘grey hydrogen’ by-product of chemical and oil industry processes may well be used.

Whilst EMU trains and city buses are different vehicles, the comparison in battery versus hydrogen fuel cells is indicative. So at this time, hydrogen fuel cell buses are typically used on routes in especially polluted corridors and cities.

So, battery buses, hydrogen buses, or both?

Hydrogen is really a means of energy storage, just like batteries and pumped storage. It is not a fuel source. But hydrogen compares poorly to those technologies, as the energy required to produce and store hydrogen is considerable. Nevertheless, despite its myriad drawbacks, hydrogen fuel cells do appear to overcome some of the drawbacks of vehicle batteries, which convinced TfL and other transport agencies to continue to evaluate fuel cell technology. To cover the spread on electric bus technology.

Both battery and hydrogen technologies still have potential to improve with additional research and development.

How the government views hydrogen vs batteries

Charged with planning for the future of transport, especially in regards to its promise to end diesel vehicle sales after 2035, the government has been studying these two electric zero emission transport technologies. We have read a number of their recent hydrogen policy reports and provide this summary:

- The government is unwilling to bet on one of battery or hydrogen for the bus and coach market. There is still uncertainty in battery technology and capability, as well as pricing. Hydrogen is viewed as more certain on these trajectories. But the current long term view (after 2035) on the split of bus/coach vehicles sold is 75% battery to 25% hydrogen overall.

- For the bus market alone, the current expectation 85% will be battery powered – the biggest issue for batteries being providing sufficient heating in winter.

- For coaches, the estimation is 60% will have batteries as the prime mover. (Hydrogen fuel cells do use batteries for storing charge for regenerative braking, but the batteries are not the primary energy source.) The biggest issue for coaches is the total battery weight to achieve long distances between charges. The average daily coach mileage is about 80km more than buses.

- Hydrogen has a better case to be used in longer range transport, such as trains and ships.

- Long term battery share is acutely price sensitive – if battery price drops enough, the expectation is that almost all HGV and buses sold post-2035 will be battery powered, as any battery impracticality is outweighed by cost. However, this does not apply to coaches for the reasons provided in point 3. Battery pricing trajectory has been be below expectations to date. If this continues, even if the curve is flatter than hydrogen fuel cells in the longer term, it will undermine the hydrogen refuelling infrastructure investment.

- Trolleybus style road wiring is under serious consideration in the UK and Europe for HGV, coaches, and buses along heavily used corridors and some motorway sections. Scania has built some pantograph HGVs to trial such an Autobahn segment in Germany <Behind Germany’s first stretch of electric highway | FleetOwner>. Even with limited overall mileage, at 750V with minimal bridge clearance required, this would be quite efficient and tilt the ratio heavily against hydrogen.

So battery buses currently have a strong lead over hydrogen buses that they are unlikely to relinquish.

The hydrogen bus RV1 history sections had been written by the late Walthamstow Writer and were updated with current developments.

Many thanks as well to NGH, Jonathan Roberts, and Ben Traynor.

This is the first of a three part series investigating the practicality and potential of hydrogen as motive source. Part 2 analysed the hydrail (portmanteau of hydrogen propelled rail) prototypes and initial trials, and Part 3 will look at current hydrail developments; clean, cleanish, and downright dirty sources of hydrogen; and numerous other factors.