Despite having one of the largest subway networks in the world, New Yorkers now experience frustratingly erratic and unreliable service. Underfunding has meant that engineers have been pushing the often-century-old subway signalling hardware decades past its design life, so breakdowns are frequent. This is all too familiar to Londoners who lived through the 1950s to the 1980s, when its transport system atrophied.

This article looks at the role of state for the art train signalling in resolving many of the reliability issues of legacy metro lines, whilst simultaneously adding considerable capacity to them. Another Reconnections article will soon look at these parallels between New York and London’s decline and renaissance in more detail.

In November 2019 the Institution of Railway Signal Engineers (IRSE) held a conference in Toronto, Canada on the topic automatic operation of trains using CBTC signalling. Whilst much of the focus was on North America, understandably given the venue, the subject is just as relevant to London. In particular, the signalling upgrade situation on the New York subway is detailed, as are recent signalling upgrades in London. During the writing of this article came the shock resignation of the head of the New York Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA), Andy Byford, ostensibly for signalling upgrade related issues.

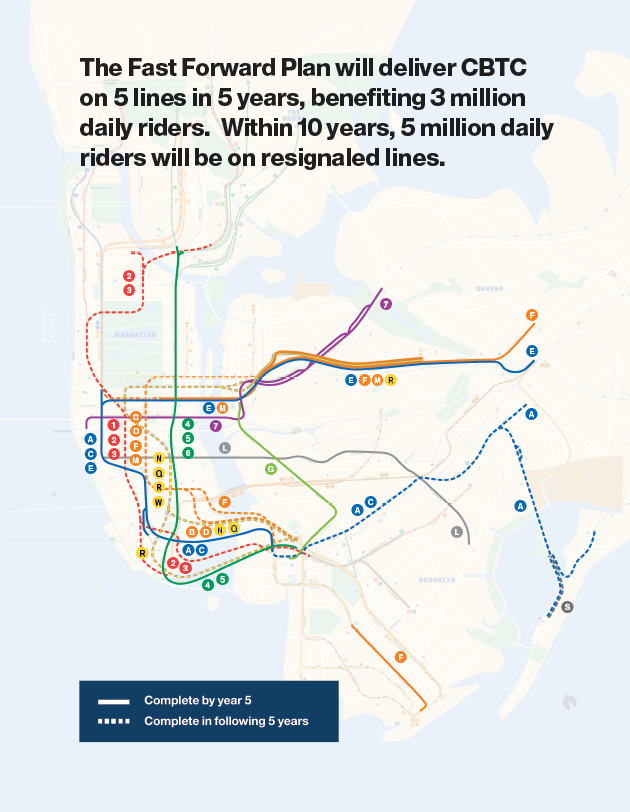

To address New York’s subway reliability issues, Andy Byford had developed his $40bn MTA Fast Forward Plan to upgrade signalling on all lines, along with other system and bus network improvements. At the core of this plan is state of the art communications based train control (CBTC) signalling, which allows agencies to wring more frequent trains out of existing tracks. CBTC is also being implemented in a number of other metro lines around the world, including a number in London.

George Clark, IRSE President

George Clark, a London Underground signalling engineer, is currently president of the UK based IRSE in a 'voluntary' role. He opened the conference by explaining how CBTC has grown in relevance:

- initially developed for and installed on greenfield urban rail lines

- evolved to handle much more complex environments and systems

- now being implemented in many different types of railway systems, such as light rail and mainline railways.

It is still evolving.

He related that initially CBTC was cautiously designed to provide 32 trains per hour (tph) reliably on the Northern, Jubilee and Victoria lines in London. But engineers soon realised that CBTC could achieve more time savings safely. With a bit more work, the Victoria line now achieves 36 tph at peak hours.

London’s Four Line Modernisation (4LM)

We recently covered the 4LM signalling modernisation, as well as the Underground's Digital Railway efforts in detail, both of which cover the capabilities and implementation of CBTC (called automated train operation - ATO - in those articles) on the Underground, as well as some of the issues.

Note that ATO is the generic term, as is automatic train control (ATC). The Thales version, installed on the Subsurface Railway, Northern and Jubilee lines, is branded TBTC, shorthand for Transmission Based Train Control. The term ATO covers CBTC and TBTC (as well as European Railway Traffic Management System (ERTMS) mainline signalling).

As stated by a number of presenters at this conference, CBTC evolution is now principally driven by customers coming up with new signalling scenarios (called ‘use cases’).

Pete Tomlin, another London Underground ex-pat

Pete Tomlin had started his signalling career at London Underground, where he worked on the Jubilee Line CBTC implementation. After that, Andy Byford offered him a job overseas in 2009 driving the installation of CBTC on Toronto’s Line 1 Vaughan extension. Tomlin then followed Byford to New York City in January 2019 to head the CBTC implementation of Andy Byford's Fast Forward Plan. This will replace the antiquated fixed-block signalling system with CBTC for more than 90% of subway riders in 10 years. This is in addition to the current capital programme which is resignalling the Queens Boulevard lines (with Siemens CBTC), which carries E, F, M and R Line trains.

At the IRSE conference, Tomlin presented his work implementing CBTC in New York. The city’s Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA) operates 473 stations on 24 subway lines, carrying over 1.7 billion riders a year. There are 818 miles of signalled track, 12,000 signals, 15,000 track circuits, and 200 interlockings, many dating from the 1930’s.

Currently two lines (43 miles) operate under CBTC:

- Canarsie L line (Siemens) since 2007,

- Flushing 7 line (Thales) since 2019.

As well, a third supplier is being qualified (Mitsubishi).

It is no surprise that the Canarsie and Flushing lines are by far the best performing lines on the NYC subway.

Tomlin's mantra, earned through years of experience, is "Track and truck mounted equipment means trouble", as undercarriage equipment is exposed to the harsh track environment, which adds to the maintenance burden. Furthermore, maintenance (and training) are key costs in keeping the system operational.

In what is turning out to be a once in a lifetime signalling upgrade, Byford and the MTA plan to eventually have CBTC operational on all of its 24 lines in 20 years. This will improve 90% of passengers journeys, and increase reliability, on:

- 220 miles of CBTC on 11 subway corridors, many with multiple lines,

- including 47 of the 50 busiest stations.

To build some quick wins and momentum, the first five years of the Fast Forward Plan would include five more lines converted to CBTC, upgrading over 50 stations to be accessible, state of good repair at another 150 stations, and redesigned bus routes.

On 13 January 2020 New York announced that the first of next CBTC line upgrades, the 8th Avenue A, C and E lines, had been awarded to Siemens. Having already worked on the Canarsie Line CBTC, this win for Siemens may lead to follow-on contracts in New York.

The next phase of the Fast Forward Plan is to build in 10 years what was previously scheduled to take 40 years.

What's politics got to do with it?

CBTC's potential doesn't come easily or quickly - it requires years of planning, intricate scheduling to keep existing services running, and hard work. Most of all, an on time and on budget CBTC implementation requires experienced hands to guide the way, managers to advocate for and obtain the agency and political buy in, and to keep other projects from impinging on budget and labour. For this reason CBTC experts are a highly sought commodity.

Some politicians like to direct their transport chiefs as if they are staff carrying out their every whim. But public transport, especially rail, is subject to the laws of physics, geography, geology, and technology. Plus the principles of human decency and managing professionals.

The experts fight back

Andy Byford's resignation from the MTA on 23 January 2020 wasn't a total shock - he'd actually resigned the previous year in October 2019, only to be coaxed back the same day.

Nonetheless there is only so much a person can take, even a patient and practical man like Byford. It appears that part of the friction between him and his superior, New York State Governor Andrew Cuomo, was due to the latter's frustration at the nominally slow progress of the CBTC implementations, even though these would be 30 years’ quicker than previous plans.

According to City and State NY, Byford decided to resign when the Governor's reorganisation plan would have left Byford at only an operational level, without the authority to carry out his Fast Forward Plan.

What Byford's resignation has done however may have started an exodus of CBTC and other management and experts. The day after Byford resigned, his hand picked CBTC expert Pete Tomlin also resigned - which was completely unexpected. Their last day will be 21 February 2020.

There is no doubt there are already many suitors for Byford's and Tomlin's talents, as CBTC is being implemented in metros and LRTs worldwide. Successful cities are based on getting people to their jobs, appointments, classes, entertainment etc quickly and efficiently.

Reconnections doesn't like to speculate, but with Mike Brown leaving TfL in May 2020, one does wonder if Andy Byford could be a potential candidate for TfL’s top job.

Tight control means lots of debugging

Back to the technical world of CBTC, where tight control is needed is in the integration of the lines, cars, and car components together so that CBTC can optimise performance. All safety-critical moving parts on each car are integrated into the CBTC, such as passenger door operation, to shave seconds off dwell time reliably, consistently and safety. Signalling is sometimes seen to politicians, the media and outsiders as a black art, but it's a highly sophisticated and highly coupled technology. Installation of automatic train operation (ATO), of which CBTC is one technology, on existing lines can take a decade or more, as lines need to keep operational throughout (so it’s worth reflecting on Governor Cuomo’s intemperacy about timescales).

As a result, integrating and fully testing ATO systems has often been problematic and has gone over budget and past schedule: London, NYC, and other cities. Each ATO implementation must tailored to the unique infrastructure and train characteristics of each line.

ATO also greatly assists railway systems to become more self aware, in terms of self-diagnostics, constant communications with other train systems, and with land based systems.

Extending CBTC beyond

Other IRSE presenters described improvements to CBTC functionality, as suppliers are enhancing their CBTC systems for increasingly diverse and complex rail environments, such as mainline railways:

- controlling different train types concurrently on the same network,

- integrating with different signalling equipment on the same network,

- reducing lifecycle costs by minimizing the number of outdoor components,

- and maximizing energy efficiency.

As cities are getting busier, roads more congested, cities are looking to maximise their rail assets. In cities with older metros, the signalling systems are decades old and are increasingly costly to maintain and keep reliable. ATO offers a step change improvement in train frequency and better reliability.

Public transport agencies want guaranteed quality of services, even in case of problems, especially when ridership grows. This has driven the evolution of CBTC, which now has greater functionality than four or five years ago. Recent enhancements include:

- the ability to access a supervisory control and data acquisition system to determine if track is energized or de-energized

- track junction and work-zone management

- automatic coupling in depot, siding and rescue modes

- more efficient recovery modes in case of software crashes, such as the remote reset of automatic train control computers

- better energy management by optimizing train synchronization at peak hours and more energy efficient speed profiles at off-peak hours

- more efficient crisis management tools in integrated control centres

- a graphical user interface

- redesigned hardware and software platforms for higher availability and better performance.

In the beginning

CBTC began with a loop based system developed by Alcatel SEL (now Thales), called SELTRAC, for the North American SkyTrain systems in the early 1980s. This used inductive loops for track to train communication, introducing an alternative to track circuit based communication.

Despite being started by one company, the benefits of train communications based signalling had widespread appeal. So CBTC has long been an open standard, to the benefit of metros and suppliers, as the competition advances the technology.

CBTC is now the gold standard of rail signalling systems, allowing cities to get up to 40% more capacity out of existing lines, without having to build a new line or dig new tunnels.

CBTC Grades of Automation

CBTC operates under the following grades of automation (GoA):

- GoA 1 - Manual protected operation, no automation (this is the basic fallback operation mode),

- GoA 2 - Semi-Automated Operation (STO), which is automatic train operation (ATO) but a driver present at all times at the front of the train,

- GoA 3 - Driverless Train Operation (DTO), typically a member of staff is on board (who may carry out door opening/closing), but not normally at the front of the train, and in regular operation does not normally have any involvement with train driving,

- GoA 4 - Unattended Train Operation (UTO).

Each Grade falls back to the next lowest level for a managed service degradation.

The following grades were achieved on the following lines:

- GoA2 Toronto's Scarborough RT 1984

- GoA4 Vancouver SkyTrain 1985

- GoA3 Docklands Light Rail 1987.

For reference, here is another London lines' automation date:

- GoA2 Victoria Line 1968

Refining the CBTC architecture

CBTC technology is evolving, making use of the latest techniques and components to offer more compact systems and simpler architectures. For instance, with the advent of modern electronics it has been possible to build-in redundancy, so that single failures do not adversely impact operations.

The latest CBTC architecture has less wayside equipment - the diagnostic and monitoring tools have been improved, which makes the CBTC equipment easier to install and replace, and, more importantly, easier to maintain.

There is now off-track signalling equipment as well, in the form of signalling centre(s), to coordinate the trains and optimise operations.

CBTC architecture has evolved to move as much lineside signalling equipment and functionality onto the trains as possible, in order to:

- minimise the number of components to maintain

- reduce wear and tear on sensors and components

- provide much more flexible software control and improved diagnostics.

Finally, CBTC systems have been proven to operate trains more energy efficiently than manual and lesser automated forms of operation.

See some CBTC advances in action

A month before this conference, Thales held an Open House at their signalling division headquarters in Toronto. A Reconnections colleague made this short videoof the displays, simulations, and interactivity there.

As an example, San Francisco’s Bay Area's rapid transit regional rail system (BART) has just awarded the installation of CBTC to Hitachi that will increase capacity 40%, improving reliability, and provide for future ridership increases. CBTC will replace the current fixed-block system from the 1960s.

Not the only advanced signalling game in the world

In Europe, railways had developed over 20 different train control systems, based on their national requirements and operating rules. In particular, the safety critical automatic train protection (ATP) systems can be non-compatible. Any through train crossing European borders has had to be equipped with different ATP systems (such as the first generation Eurostars). Sometimes, it even required changing locomotive or driver at frontiers, as each country typically has its own signalling system for which the drivers have to be trained.

The additional ATP systems take up a much space and weight on-board, and add travel time plus operational and maintenance costs. Unifying the multiple signalling systems would streamline freight and passenger rail services across borders, minimise technical problems, reduce costs, and increase competitiveness.

So in 1989, European Transport ministers decided to develop a single train control system standard to apply across Europe, which became the European Train Control System (ETCS) specification. ETCS is the signalling sub system of ERTMS. Other sub systems include traffic management (ie the control system). ETCS currently provides ATP through the real-time monitoring of movement data, precise train location, and braking curves:

- ETCS Level 0 - line not equipped with any train control (ERTMS/ETCS or national) system.

- ETCS Level 1 - train operating on a line equipped with Eurobalises and optionally Euroloop or Radio infill.

- ETCS Level 2 - train controlled by a Radio Block Centre, with train position and train integrity proving performed trackside with Eurobalises and Euroradio.

- ETCS Level 3 - similar to Level 2 but with train position and train integrity supervision based on information received from the train.

ETCS levels 0, 1 and 2 are NOT moving block - this is reserved for Level 3. Note that the overwhelming majority of installations to date are NOT Level 3.

In 1996, the EU decided that European Rail Traffic Management System (ERTMS) would become the signalling standard for all high-speed and conventional railways.

What is ERTMS?

ERTMS is based on the ETCS, combined with GSM-R (Global System for Mobile Communications – Railways), the radio standard for voice and data communication over a dedicated frequency:

ERTMS = ETCS + GSM-R

Despite their names there is nothing intrinsically European about ETCS or ERTMS. In fact the country with the most miles in operation is China, and there it probably exceeds the entire European track mileage.

ERTMS is similar to CBTC in that both are moving block signalling systems. But ETCS and ERTMS are designed to be truly inter-operative, such that the individual system can be interchanged, and is not proprietary to the supplier.

Similarly, the EU mandates that all new signalling on inter-operative main lines be ETCS, with the option of ERTMS overlay.

Why is this important?

The critical part of ETCS and ERTMS is interoperability. London Underground can be exempted because there is a low chance of a main line railway operating on them. Whereas the East London Line (ELL) is an example of joint NR/LU specification of trains and infrastructure, where some form of ERTMS in its central section might be seen this decade if plans to increase ELL frequencies are taken forward.

Also, despite leaving the EU, the UK use of this standard is unlikely to drastically change. The UK's Rail Safety and Standards Board (RSSB) also had a significant role writing the ETCS standards. London’s Heathrow Airport tunnels' Belgian ATP system had to be replaced with an ETCS system to allow Crossrail's Class 345 trains to go to Heathrow, scheduled for full service in the May 2020 timetable. And to upgrade the Northern City line to Moorgate to ATO, ERTMS will be the only option.

Even Crossrail's central section should have been ERTMS. It only received an exemption because ERTMS hasn't yet evolved sufficiently to provide the required frequency, passenger door interfacing, and stopping distance accuracy.

Whilst CBTC has been in operation since the mid 1980s, ETCS and ERTMS are relatively new technologies, starting a decade and a half later. For instance, the stopping accuracy is almost where it needs to be for Thameslink, once ETCS becomes quite cheap solution for many low/medium frequency metro systems.

Not signalling rivals

In Europe, CBTC is only used for metro and light rail lines separate from the main railway network. In the UK, CBTC will likely be used only for urban rail lines, while ETCS and ERTMS will mostly be used for UK mainline railways. In the rest of the world, CBTC is pretty much restricted to metro and light rail systems, plus some North America mainline railways.

CBTC Signalling for LRTs

Perhaps surprisingly, CBTC is also relevant for street-running light rail. Modifying CBTC for LRT lines in mixed traffic segments is a recent innovation, to avoid collisions with vehicles and pedestrians, and to synchronise with traffic lights. This task is an order of magnitude more complex than a fully closed system.

Despite the complexity and considerable software development costs this will entail, this investment is deemed to be sufficiently beneficial, as higher capacity, safer operation, and driverless depot operation will lead to long term savings.

CBTC for mixed traffic LRT requires implementation and integration of front and side sensors for collision avoidance at level crossings and around traffic. In addition, automotive accelerometers and speed sensors are used instead of wheel turn counters for more accuracy, so that wheel slip no longer affects train position accuracy.

A good example of the flexibility and breadth of modern CBTC functionality is Bombardier's CBTC installation system on the Eglinton Crosstown light rail line in Toronto. The system will incorporate three levels of automation: manual and automatic train protection (ATP) along street areas, automatic train operation (ATO) in the tunnels, and unattended train operations (UTO) in the depot.

Neither snow, nor sleet, nor level crossings can keep us from our appointed runs

Many mainline railways still have level crossings. So obstacle detection needs to be included in CBTC functionality for such lines. Using laser detection and rangefinding (LiDAR) is expensive (€120,000 per crossing), and it cannot always detect small or low objects. They can also affected by adverse weather such as heavy rain, snow etc.

Hence multiple detection systems are required, such as infra-red cameras, along with sophisticated software to reconcile the different views and to filter out nuisance signals.

Further CBTC enhancements planned

Virtual coupling together of trains is being studied to maximise track utilisation, such that a flight of trains is controlled together, not individually. This works ideally with the same or very similar train types, but even braking characteristics can vary between trains of the same class.Obviously, joining and splitting of trains adds another level of operational complexity.

Overall, Britain's railways are transitioning – slowly – to become a ‘More Intelligent Railway’. Moving block signalling is one basis upon which it will be built.

In conclusion

London Underground and other cities worldwide have proven ATO’s effectiveness in adapting to a breadth of environments and operating regimes. New York will get there, despite personality clashes. The cautious main line environments for automated passenger operations may take longer to resolve, though Thameslink’s ETCS Level 2 is now starting to prove its worth on the core section of cross-London services, at a 20 tph frequency.