A revival of airship technology has been foretold for decades. Until now, it hasn’t delivered more than illustrations and a few empty hangars. Recent advancements in aerospace technologies and demand for decarbonized aviation have led competing airship companies to finally take the next step. Now, they’re flying the largest airships since the Graf Zeppelin II in 1938.

The question is, how do these companies turn prototypes into a functional business?

A schism has formed in this emerging field of competitors. Some airship manufacturers and airlines are targeting the tourist and luxury markets first, such as OceanSky Cruises, Air Nostrum, Hybrid Air Vehicles, and Atlas. Others, such as LTA Research and Flying Whales, are pursuing cargo and logistics applications. A business is in greatest peril at its start. Thus, the disagreement on which initial role to pursue is the sign of a truly important dilemma facing this nascent industry.

Crucially, the first-mover advantage in this space is enormous. Whichever company succeeds in fielding its first vessels to customers will be able to cut costs and scale up before its rivals. Airships can easily convert between passenger and cargo configurations, just like airliners. Success in one market would soon lead to a dominant advantage in the other.

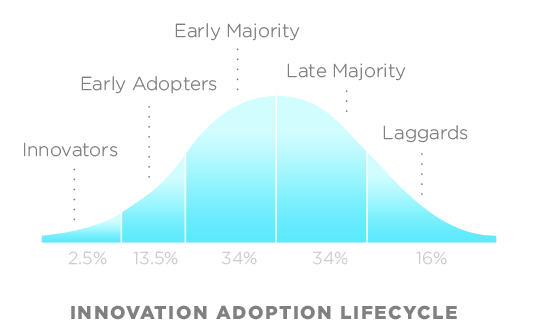

The technology (re-)adoption curve

From a launch customer's standpoint, it is almost immaterial that an airship is more efficient than an airplane or helicopter. Existing aircraft benefit from decades of mass production, enormous subsidies, established infrastructure, billions in capital, and amortized research and development. These all combine to erode or even reverse airships’ inherent cost advantage.

On top of that, there are priceless human factors. Airplanes benefit from an expert labour pool, customer relationships, and cultural normalisation. Hence, the subset of ‘innovators’ who would even consider airships in any given market is minuscule.

Thus, luxury and cargo airships target the niches where they have the greatest starting advantage. Despite sharing that fundamental strategy, there are important differences in both approaches.

The case for cargo

Cargo applications may seem like the more practical, serious application of airship technology. After all, the era of overnight trains and ocean liners dominating mass transit is over. Those luxurious leviathans were slain by the peerless speed of jet travel. By contrast, container ships and freight trains are alive and well.

Cargo hauling is a far larger market than luxury travel in nearly every form of transport. It can thus seem like an anachronistic frivolity to revive passenger airship flights. It's a minuscule market, one that’s kept on life support by a handful of small sightseeing Zeppelins in Germany.

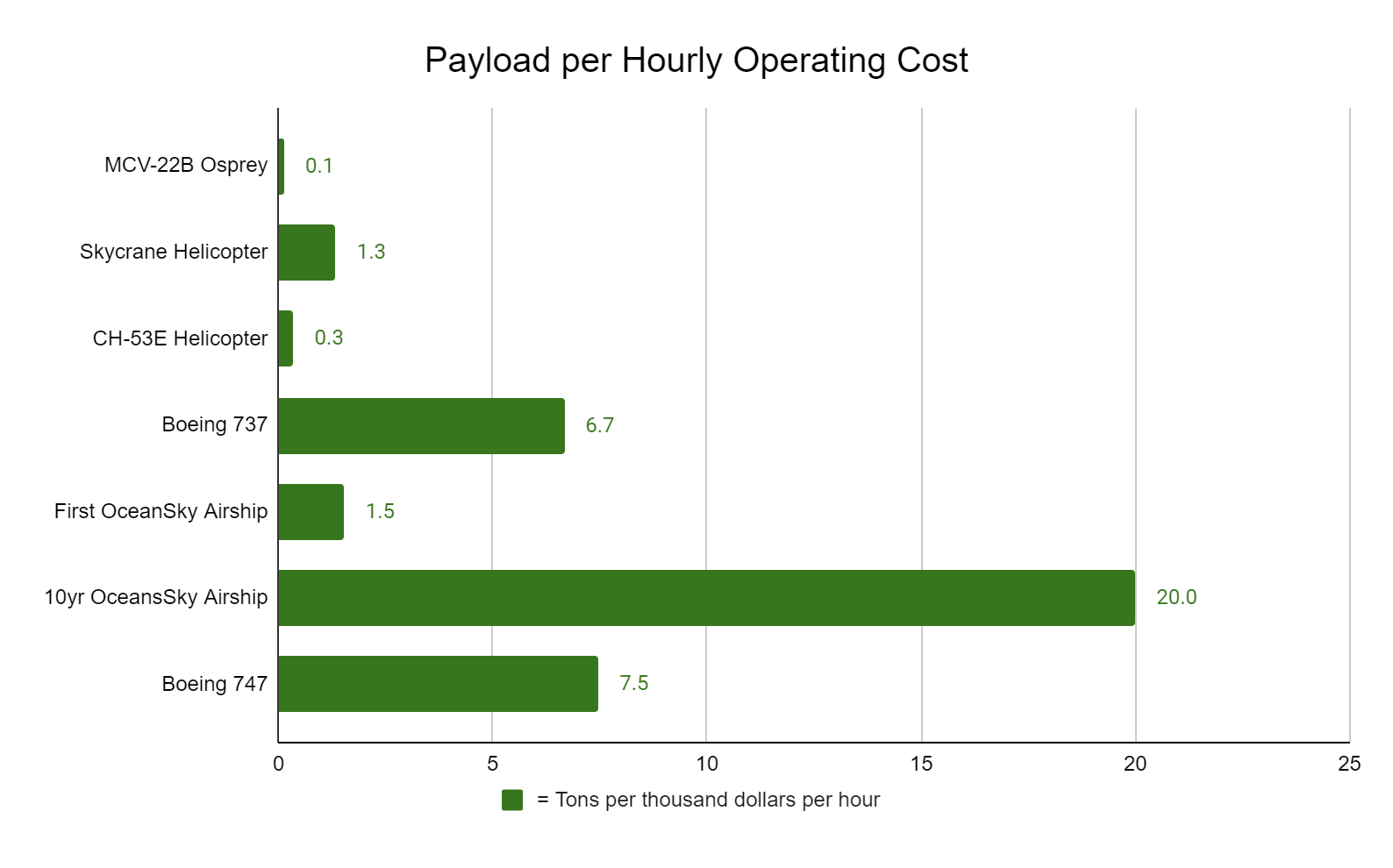

Airships seem like nearly ideal cargo aircraft. They hover easily, almost never run out of internal space, need little destination infrastructure, and can efficiently carry an immense amount of weight over incredible distances. Today, the air cargo market is mature enough to support niche cargo aircraft, such as outsized cargo planes and heavy-lift helicopters. Flying Whales ltd. claims cost reductions of 58-86% compared to these specialized logistics aircraft. This would provide breathing room for healthy margins starting out.

Although airships would initially outperform large rotorcraft, they would not be able to compete with cargo airliners for years, according to OceanSky Cruises' operating cost estimates in AIRSHIP issue 198, US DoD.

The primary risks of this strategy are scale and alternatives. The specialised cargo aircraft which airships could best replace—such as the Super Guppy, Boeing Dreamlifter, and Airbus Beluga—are vanishingly rare. Fewer than twenty of these airplanes operate in the entire world. By contrast, swarms of cargo aircraft like the Boeing 737 are thick as midges. They’re as optimised and cheap as they’re ever going to get. Likewise, airships have to compete with ground and water-based transport options simultaneously.

This drastically restricts cargo airships’ initial markets. At best, they can operate in remote areas, but those tend to lack the capital and/or risk tolerance required to bootstrap such an endeavour.

The business case for luxury travel

Despite their advantages, airships never became widely used for cargo in their heyday. This was partially due to infrastructure and technological limitations, but the primary reason was opportunity cost. Luxury travel could command much higher revenues, and still does today. For instance, the container shipping industry recently posted 6.1% profit margins, and cruise lines like Royal Caribbean are pretty healthy with 23.3% profit margins. Cargo operations in general vary quite wildly in their profit margins, depending on global instability, tariffs, pandemics, and whatnot. The cruising au contraire usually has higher, more consistent profit margins.

Putting aside margins, the markets themselves are dissimilar. The “adventure tourism” market OceanSky Cruises targets is over $480 billion and growing by over 15% annually, as opposed to air cargo’s $110 billion and 4%. This creates a much larger pool of potential opportunities.

Almost all technologies are first marketed to the rich, and for good reason. Even when massive companies believe they can deviate from this strategy, they're often wrong.

For example, major automakers' first attempts to reintroduce electric cars failed. They targeted the low-margin economy car segment first, relying on electric cars’ simplicity and efficiency. However, they were unable to compete with gas cars' economies of scale. Starting in 2008, luxury electric cars were able to unseat these incomparably larger competitors by going upmarket. They took these high margins and reinvested them to improve their technology and lower costs.

The physical advantages of luxury

Aside from markets, there are more basic reasons to pursue a cruise application before logistics. A cargo role benefits from airships’ efficiency, spaciousness, and flexibility. Not only do those advantages carry over to cruising, it also benefits from low noise, negligible turbulence, and easier buoyancy compensation. Cruising also depends far less on speed.

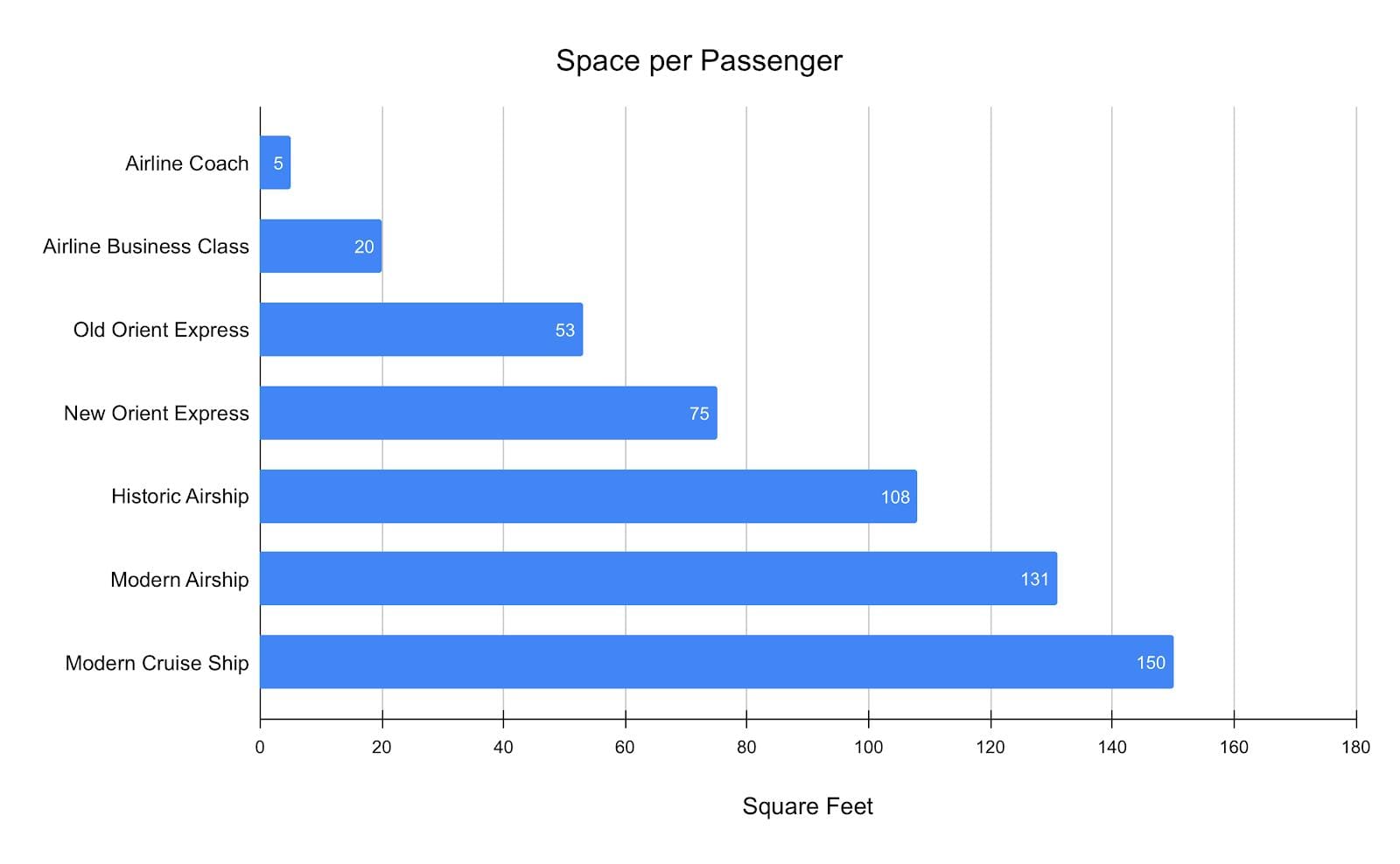

Just as time is money, space is comfort. Spaciousness and interior flexibility are the areas where other aircraft cannot match airships. Unlike trains and planes, an airship’s interior design isn’t constrained to the form of a narrow tube. Their public rooms can be as cavernous as an ocean liner’s, spanning several decks and covering thousands of square feet. In their heyday, airships were described as “intermediate in comfort between a [luxury train] and an ocean liner.” This was no idle boast:

Even modestly-sized airships like the Airlander 10 have several times more interior space than comparably priced airplanes. The Airlander costs $42 million, less than a Gulfstream G500, but it has over six times the passenger space—just as much as the $185 million Boeing 767-300.

Beyond these practical reasons to pursue luxury applications first, there is a separate category of “soft factors” that cargo airships lack. “Soft factors” such as comfort, aesthetics, and emotional appeal are vitally important, despite being difficult to measure. Humans are not perfectly logical robots, therefore soft factors are, in fact, pragmatic considerations.

Flying: A postmodern hellscape

Early 20th century air travel was synonymous with glamour, romance, and adventure. It was a profound experience, one which spurred even the most dour people to wax poetic about it. What that modernist era lacked in caution and engineering prowess, it made up for with optimism, passion, and ambition. Nowadays, though, air travel has transformed into an artless, joyless, soulless experience.

Modernism's hubristic downfall during the Great Depression and World War II birthed our postmodern era of relativism, cynicism, and irony. Now, postmodernity struggles with the death of meaning, causing many to feel alienated and adrift. The death of meaning affects many of the objects and products we engage with, which have become less special and more disposable over time. This is nowhere so apparent as in air travel.

Is the above photo a sight that conjures to mind “first class?” Or befits the majesty of flight for that matter?

Modern airliners are so effective at generating ennui, they manage to sap the joy out of what ought to be an objectively magical experience. This is not the dream of flight that has captivated the souls of humanity since the dawn of our species. This is a gross, degrading, cramped, overcrowded bus with wings. Worse, airliners are a pollution source that is coming under increasing scrutiny from governments and activists alike.

The debasement of flight isn’t only a matter of airlines chasing the lowest possible ticket prices, either. It's a shift of attitude, combined with the inherent physical limitations of airplanes. Even private jets, with their nigh-limitless resources, compete to be as inoffensively beige as possible:

The boldest artistic choice in the above photo is the use of “Ecru White” instead of “Eggshell White.”

These aggressively monochromatic private jets aren’t designed for style or aesthetics. They’re designed to be unobtrusive, so that passengers can insulate and distract themselves from the discomfort of air travel. However plush and padded, though, a private jet is still going to be a cramped, noisy tube at the end of the day. Flight has become a means, not an end in itself.

In backlash, opportunity

The dreary, punishing experience of air travel creates its own backlash. Airlines and their various torture devices are the punchline of countless jokes. This creates a prime opportunity for airships to exploit. There is a huge, growing demand for a different kind of luxury—not material goods, but rather meaningful experiences.

Airships slot into this role perfectly. Their open, majestic interiors, smooth ride, and wondrous ability to go just about anywhere can provide awe-inspiring voyages to an overstressed populace that’s sick and tired of being pessimistic about the future. Unlike planes, airships are also extremely environmentally friendly, further enhancing their futurist appeal and alleviating the guilt normally associated with luxury consumption.

The question is whether people can again be convinced that something as outlandish as an airship can fill that void. The more people considering airships as an option, the better, but gaining positive attention demands that airships leverage their grandiosity and aesthetics for all they’re worth.

Launched in 2018, Belmond’s Orient Express Grand Suites are the exception that proves the rule of “they don’t make them like they used to.”

During the airship industry’s infancy, when costs are highest, the best competition is zero competition. To survive, they must master the art of creating unique, breathtaking experiences that cannot be found anywhere else in the world.

The power of captivation

Hybrid Air Vehicles' (HAV) Airlander 10’s spectacular sky bar takes advantage of the ship’s low altitude and speed to allow for massive windows and unparalleled views.

An underappreciated advantage of luxury products is that they're aspirational, fashionable, and captivating. When done right, prestige products generate their own priceless consumer interest and marketing.

An airship is a million times more attention-grabbing than any billboard, sports car, or superyacht. The sheer size and surreality of seeing something literally as massive as an oceangoing luxury liner, and used for the same purpose, hanging suspended in the sky overhead as an airship — is a sight completely foreign to most people, passed almost completely from living memory. This has the potential to “go viral” on a massive scale.

Small airships are exponentially less efficient than large ones, so airships will always be relatively rare. Airships cannot replace all aircraft, but standing at aviation's pinnacle has its advantages. It helps to avoid them becoming mundane.

Throughout history, many inventions owe themselves to daydreams and science fiction. Great aviation pioneers, such as Alberto Santos-Dumont, were directly inspired by childhoods of reading the wondrous visions of the future in Jules Verne’s novels. As fanciful as it might seem, fantasy and wonder pay out real dividends over years and decades.

Reconstruction, not resurrection

There are lessons to learn from bygone glamor, but nostalgia can be a trap. Proposals to resurrect wooly mammoths or replicate the Titanic have always been rooted in the quixotic idea that the past can be recaptured authentically. Such things cannot be perfectly replicated, and even if they could be, the copies would be bereft of their original context. So, too, must airships be designed for the future, not the past. The 20th century is over, and it isn’t coming back.

Ironically, a forward-thinking attitude would most faithfully preserve the modernist spirit of airships, not slavishly copying the past. That’s better left to museum exhibits, not working aircraft.

Ocean liners, sleeper trains, airships, and supersonic jets were all once the fastest way to travel long distances. One thing they all had in common was that, despite their prestige, comfort was secondary to speed. In the 21st century, cruise ships and luxury trains forgo speed altogether, making comfort their first priority. So, too, must airships.

Counterintuitively, dreaming of all the amazing things airships can do is the most pragmatic way to make them successful. Their “magic” has always been their strongest weapon, and it still endures after all these years. That magic is why passionate enthusiasts such as Bruce Dickinson and Sergey Brin fund these airship projects to begin with. Humans are creatures of imagination, and we’re capable of great achievements—but only when we’re sufficiently inspired. That is why the next generation of airships must dare to be grander than they ever were before.