The Stansted Airport Track Transit System (TTS) will be decommissioned in 2026 after 35 years of airside operation at the London airport.

This people mover system debuted as a novel piece of transit infrastructure when it was introduced in 1991, and in this post we’ll take a look at why it was built, what problems the TTS was intended to solve and why it’s being sunsetted a quarter of the way through the 21st century.

Why a People Mover?

At airports prior, passengers would be expected to walk to the gate, perhaps with the assistance of long travelators which would allow travellers to either take a break and stand still, or proceed at twice the normal walking pace.

But as airports were becoming larger and more ambitious in their design, they began to resemble small cities in their own right. Travel times between terminals, as well as distances between departure lounges and gates were increasing with the size of the airports. And if we were to take the small city metaphor to one of its natural conclusions, then cities need frequent, reliable transit.

Stansted airport had humble beginnings. Opening in 1943 as Stansted Airfield, it was later rechristened RAF Stansted Mountfitchet in 1943 when it saw use as a base of operations during the Second World War by both the Royal Air Force and the United States Army Air Force.

After the war the airfield was returned to civilian hands, and in 1966 the BAA (British Airport Authority) took control in order to provide a de-facto third airport for London to supplement Heathrow and Gatwick, with the main intention of using it for package holiday operators. In 1985, permission was granted to make Stansted officially London’s third airport, after Heathrow and Gatwick. But doing so meant redeveloping the humble airfield into a modern airport with the capabilities of handling large amounts of traffic.

The airport building would be designed by Norman Foster’s architectural firm Foster Associates. The structure of the airport would consist of the main airport building, housing the check-in and arrivals area, security, customs, and the airside departure lounge.

It was decided the airport would need a railway connection to London from the outset, and doing so required building a spur from the West Anglia Main Line allowing for a direct connection to Liverpool Street.

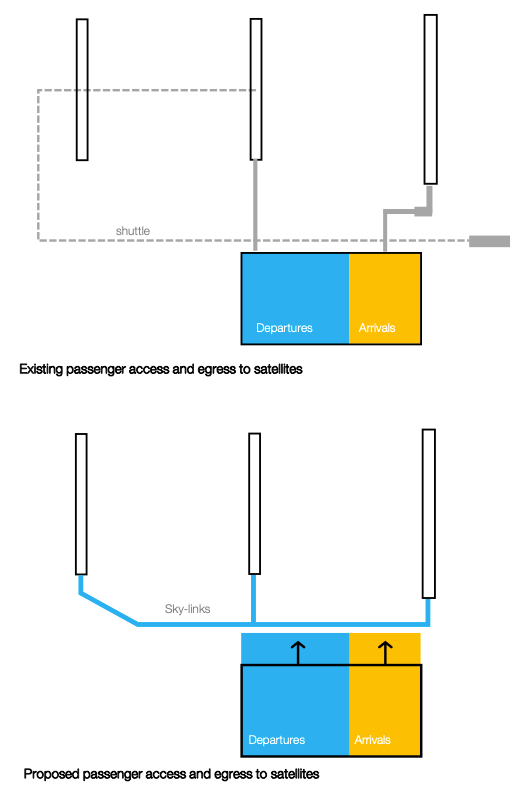

Back on the airfield, planes would arrive at gates located at two satellite buildings separated from the main airport terminal. This posed the interesting question of how departing passengers could best be moved from the departure lounge in the main building to the two satellites, as well as by what method arriving passengers could be transited from their gate to either the domestic arrivals area or border control. In fact, there was a need to separate the two types of travelling passenger: domestic and international.

The twin problems of transiting passengers to the satellites and keeping domestic and international passengers separated resulted in the novel idea of an airside transit network.

A Potted History of Airport People Movers in the UK

I have memories of being around 9 years old at Gatwick Airport’s South Terminal. It was in the early hours of the morning and I was heading on holiday with my family. It was still dark outside and our flight had been delayed, but when the boarding gate was finally announced there was a crush of passengers racing from the airside departure lounge to make it to the satellite terminal. After a brisk walk with the crowds we all waited in front of what looked like a bank of lift doors. When they opened we were last in, and as the doors closed there was an announcement to hold on to something. And then the “lift” started moving sideways. For a moment I thought I was living the Wonkavator, but no. I’d unexpectedly experienced my first airport people mover.

The people mover described above no longer exists. It was installed airside in 1983 to shuttle passengers between the Gatwick South Terminal main building and a smaller satellite, and was also the first of two people movers installed at Gatwick. Critically, this was the first system of its kind in the UK.

In fact, it claimed a lot of firsts: It was the first self driving train in the UK – the Docklands Light Railway wouldn’t open for another four years until 1987. It was the first UK system to have platform screen doors, opting for the opaque Moscow Metro style “vertical lifts” rather than the transparent doors we’re used to seeing today.

In 1987, a new North Terminal opened at Gatwick, and a need to connect the two arose as not only were they some distance from one another, but the railway station was located at the South Terminal. A second people mover system was installed, this time landside. Unlike the one in the South Terminal this one still exists and underwent significant refurbishment between 2008 and 2010. You can of course ride it without needing a plane ticket.

Other people mover systems followed. At Birmingham Airport (1984 – a maglev!) and then of-course at Stansted. Heathrow received one too when Terminal 5 opened, completely underground and similar in nature to Stansted’s by serving two satellite terminals (2008). Luton Airport also received a cable-hauled people mover – the Luton DART or “Direct Air–Rail Transit” (2023).

Other developments saw Gatwick’s South Terminal transit retired in favour of walkways and travelators, and meanwhile (as already mentioned) the land-side shuttle between the North and South terminals received an upgrade. Up at Birmingham, the original maglev system was eventually deprecated in favour of a more conventional cable driven system, now known as the Air-Rail Link.

If we were to group the UK’s people mover systems into two categories, there would be those where the vehicle does a single back-and forth move between two stations on a single track (Gatwick, Luton, Birmingham¹) and those whereby vehicles can freely switch tracks and potentially take different routes (Stansted, Heathrow).

By my reckoning this leaves Stansted’s TTC as the oldest people mover system in the UK which remains in its original state… at least at time of writing.

An Airside Transit Network

Fran: “… and then we change again at… Stansted.”

Manny: “I’ve always wanted to go there.”

Bernard: “Nice, is it?”

Manny: “They’ve got these little trains that have no driver.”

Bernard: “Lovely!”

– Black Books, “A Nice Change”, 2002

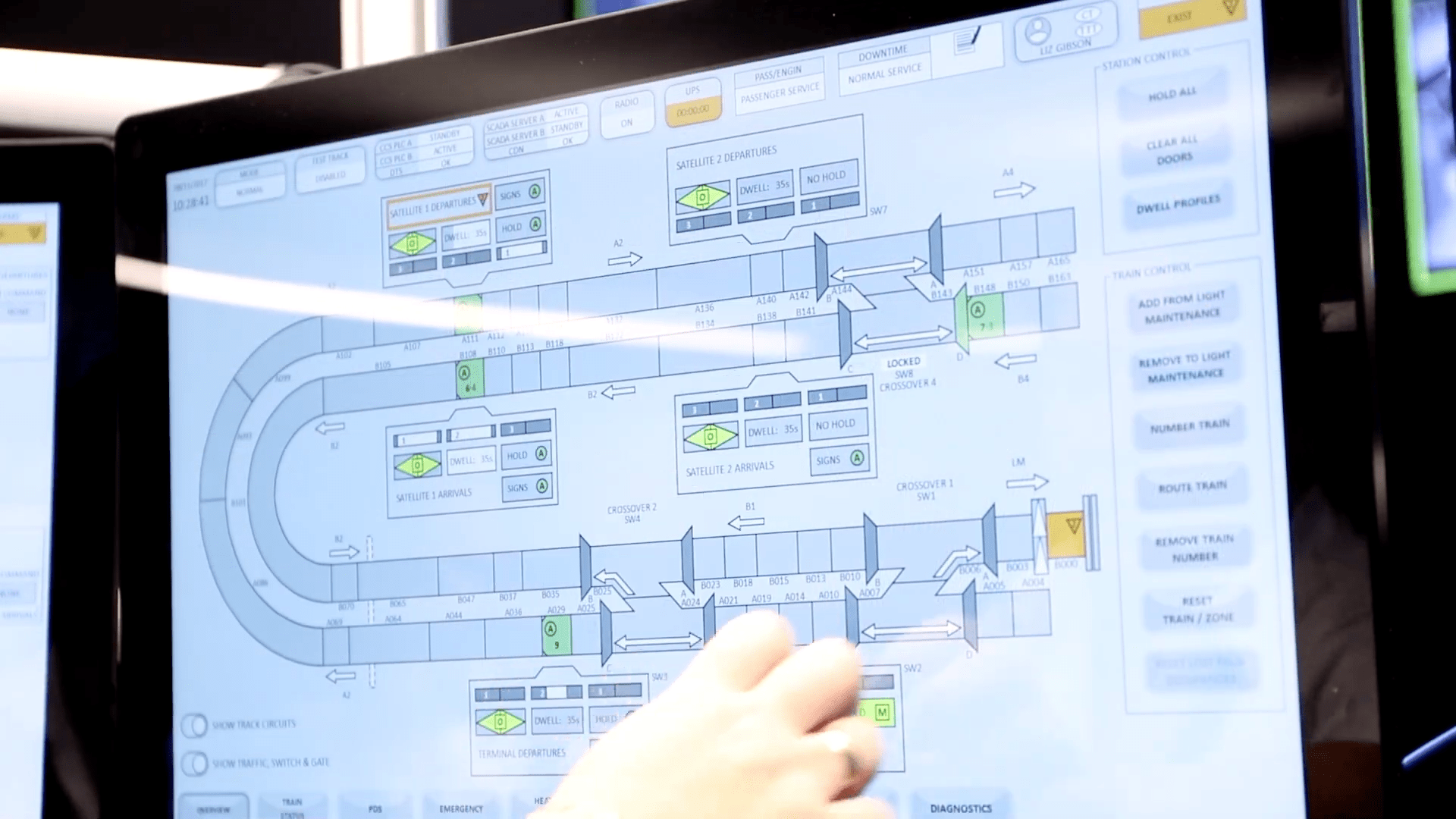

We’ve briefly covered why the original architects of Stansted chose to install a people mover. In short, they needed a method to keep domestic and international travellers separated in such a way which would deliver international travellers to exactly the locations they were expected to be, without allowing them to backtrack or end up somewhere they shouldn’t. In this way, we can think of the TTS as a system of valves for passengers, forcing circulation within the system in only the desired directions.

The idea of using a modern rail system to move people around an airport was also becoming popular in the United States and in Europe, and such a system with its automated vehicles and platform screen doors was ahead of its time when compared to other transit systems around the UK. For example, the first occurrence of platform doors outside of an airport wouldn’t be seen in the UK until the opening of the Jubilee Line Extension in 1999. Now we see these technologies being commonplace in new or modernised systems, but at the time they appeared cutting edge.

Track Layout

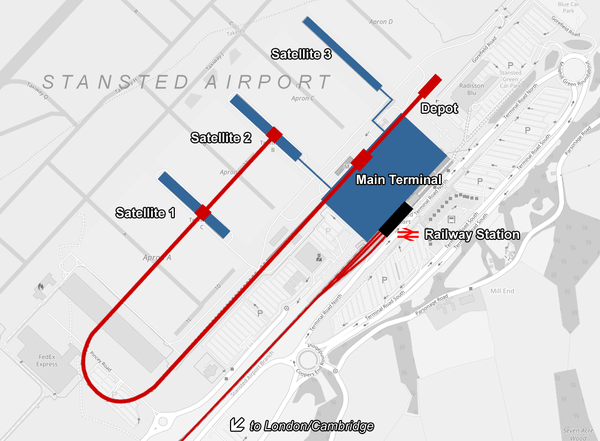

The initial system when inaugurated in 1991 served the depot, main terminal building and the first satellite. In 1998 it was extended to serve the second satellite as well.

The main terminal building consists of two stations: One for departures, and another for international arrivals. In departures, the station is connected directly to the departure lounge meaning even domestic travellers can get a close-up view of the rolling stock as they travel alongside the building.

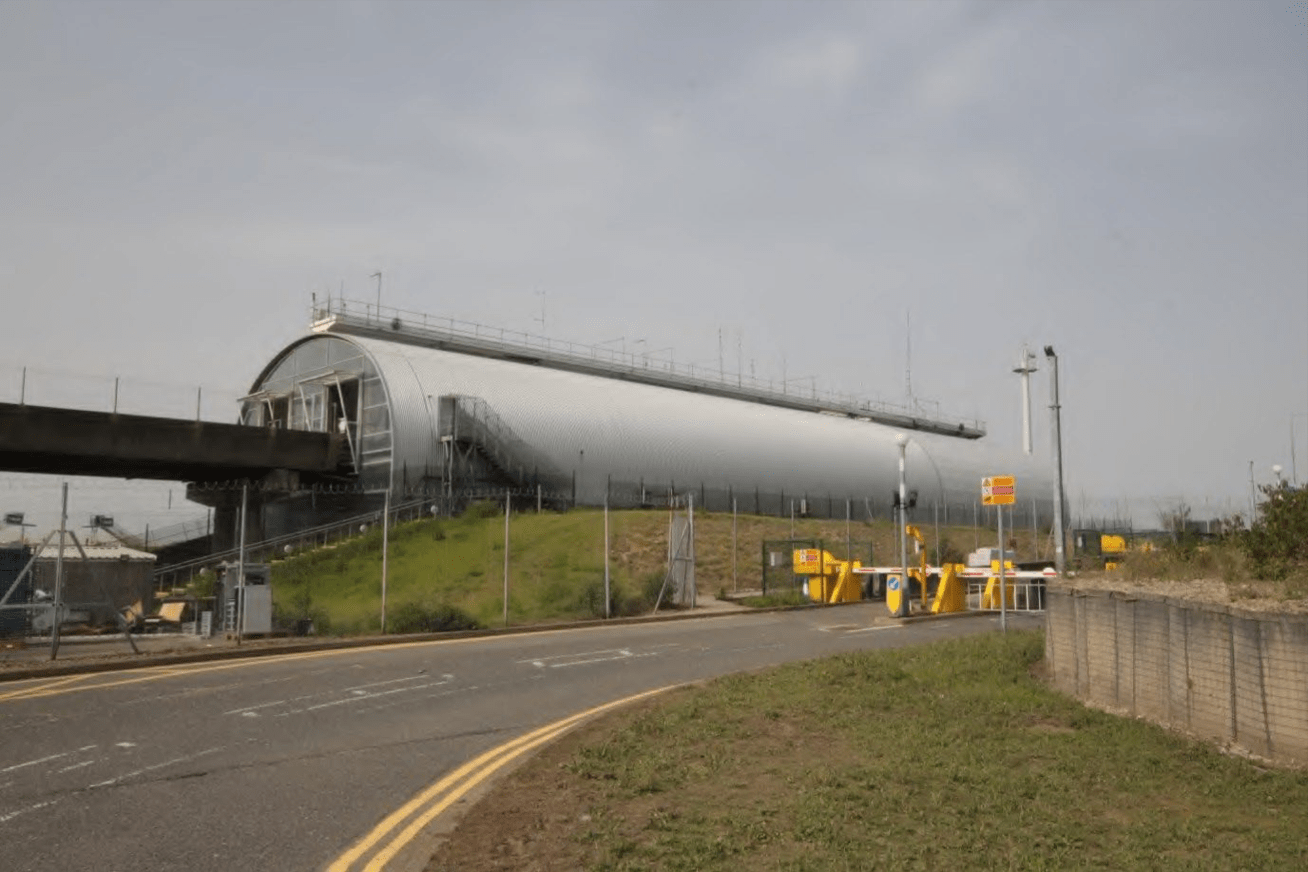

If you were to board one of the trains at the departure lounge, you’d find yourself departing to the southwest, adjacent to the terminal building, then descending into a tunnel. Once underground, your train would make a sharp 180° turn to the north west before arriving at Satellite 1’s underground station. Remain on the train and you’ll continue to Satellite 2 where the remainder of the passengers will disembark.

If you’re arriving on an international flight, you’d board the train at either Satellite 1 or 2, at separate platforms to departing passengers. Your train would then bring you back through the tunnel on an adjacent track, arriving above ground to pull alongside the main terminal.

As your train is on the track furthest away from the terminal building it will travel past the departure lounge boarding point and then move over a track switch onto the other track, pulling in to the station at arrivals. All passengers would be expected to disembark, which would bring them right into the UK border control area. The now empty train would then move back in the opposite direction to pick up more passengers from departures.

We can see how the system is surprisingly involved considering its small size and four stations. It has track switches, a train depot and a signalling control centre. It’s run like a railway, and the airport demands its fluid operation in order to function.

You’ll note that Stansted has three satellites. Numbers 1 and 2 are served by the TTS, and numbers 2 and 3 are connected by an air bridge. This creates an oddity whereby Satellite 2 in fact serves both domestic and international travellers with shared gates, with domestic travellers arriving via the air bridge on the upper level, and international travellers arriving via the TTS on the lower level.

Rolling Stock

The TTS is operated by Bombardier CX-100 vehicles which had their bodies built by Walter Alexander in Filkirk, Scotland. They were then assembled by Westinghouse in Pittsburgh in the US. The CX-100 model has been used in places as diverse as Singapore, Kuala Lumpur, Rome and Frankfurt, as well as many locations throughout the US.

One of the selling points of the model was that it came with Bombardier’s proprietary “CITYFLO 550” Automatic Train Control (ATC). We’ll talk more about the train control shortly, but as for the vehicles themselves they were designed for high throughput and short journeys. The inside of the vehicles have lots of space for passengers with bulky suitcases with level boarding at the stations (at the time, level boarding onto a train was rare in the UK, and unfortunately this continues to be the case)

Large windows, especially at the front, provide passengers with views over the airport’s apron… at least for the part of the journey which isn’t underground. Like the Docklands Light Railway, travellers can have a forward-facing view on the ride to their gate, a feature of the system which has no doubt delighted many users over the years. In fact, if you don’t expect to be taking an international flight before it closes, you can take a virtual journey to see what the experience is like for yourself.

The vehicles were designed to provide smooth rides, making use of rubber tyres with a guideway to direct the vehicles (similar to the Paris and Montreal metros). They have climate control – helped by the use of platform screen doors to prevent the interior environment of the train coming into contact with the outside. They were also intended to be rugged enough to survive high usage for many years. After nearly 35 years of service, Stansted’s rolling stock has certainly delivered on those promises from the manufacturer.

Maintenance and Signalling

A maintenance depot to the north-east of the main terminal allows for the storage of a spare train should a defective set be taken out of service and need to be substituted.

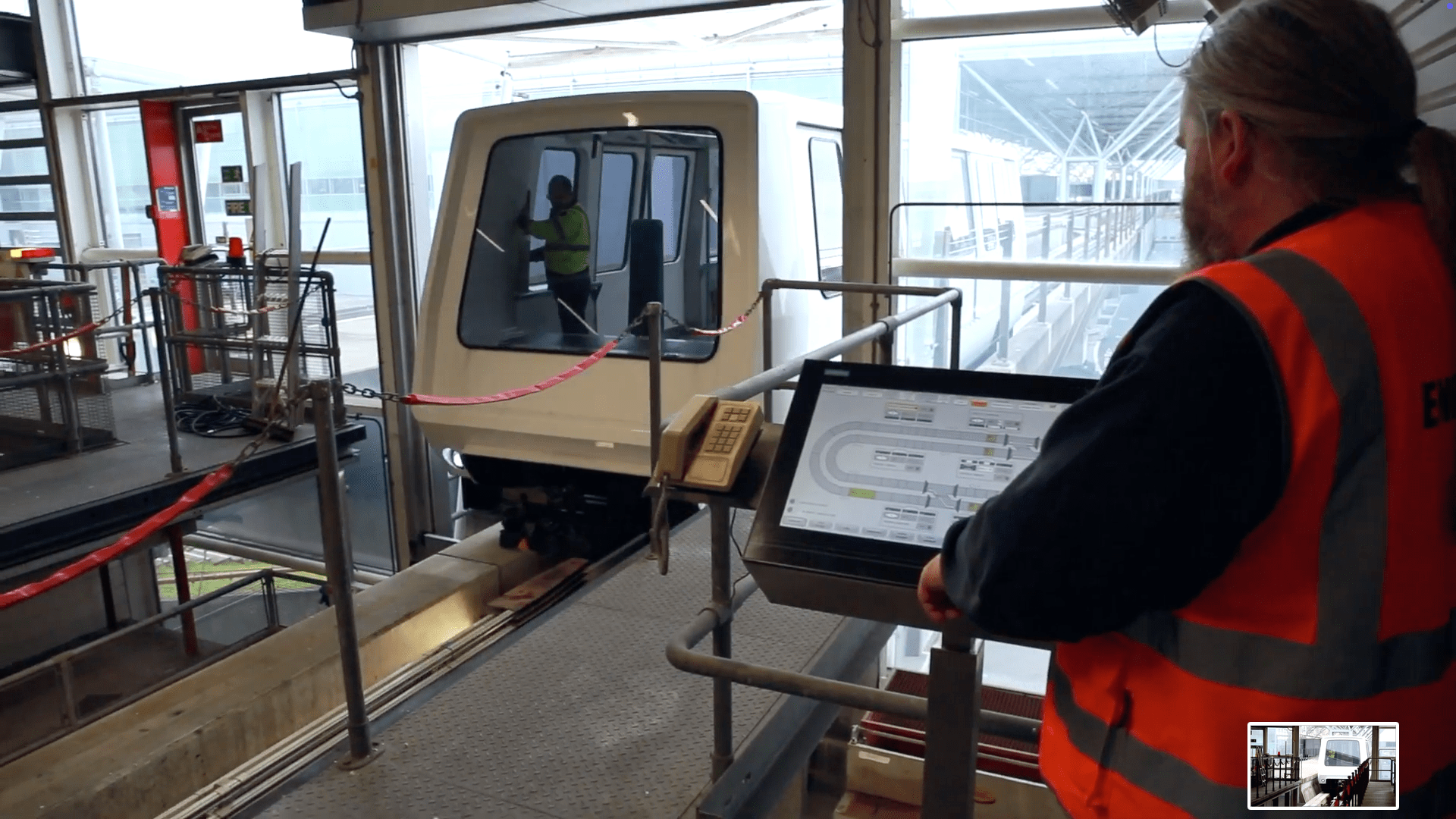

In 2017, parts of the train control system’s interface were upgraded by Firstco, an engineering consultancy firm with a specialisation in control and communications. They had already been involved in the original Heathrow Express project as well as the new Terminal 5 station for the Heathrow Express and the Piccadilly Line. More recently they’ve also been involved in Crossrail and the Northern Line extension to Battersea Power Station.

The existing system which was based on 1980s’ technology was beginning to fail, with replacement parts being harder and harder to come by (no doubt this is a situation in which signalling engineers on the older parts of the Tube network would empathise with).

Their involvement in upgrading Stansted’s TTS focussed on new workstations and an upgraded central control system, helping to extend the life of the small network for almost another decade. The solution was developed with input from the operators, and evidently there was a considerable amount of reverse engineering the existing system before the new solution could be developed. All this was done whilst keeping the TTS running.

One might at this point be tempted to point the finger at the TTS and utter the word “gadgetbahn”, and indeed the TTS does demonstrate one of the biggest challenges of such systems, which is its bespoke nature. This problem has been solved in other places around the world by using the same technology in airports as is used in city rapid transit. For example, France commonly uses the VAL (Véhicule Automatique Léger) system around the country, where exactly the same technology serving travellers at Paris-Charles de Gaulle Airport can be found serving commuters in Lille and Toulouse.

We could therefore envision a complete replacement of the TTS using a more commonly used rapid transit technology, but that is not the plan for the future.

The Decommissioning Phase

At the end of 2026, the TTS at Stansted will run its final service. A desperately needed expansion to the airport will require the main terminal to be extended forward to provide more space. As a result, construction will need to happen over the current alignment of the TTS.

Although the control systems interface had recently undergone replacement, other parts of the system are reaching end of life, and it was deemed prohibitively expensive to replace the entire network with a new one.

Therefore, in lieu of a new transit system there will be implemented a so-called “Sky Bridge”, which is just a fancy name for a new walkway connecting the three satellite terminals to the main terminal. Instead of taking a train to their gate, passengers will walk. During the period between the decommissioning of the TTS and the opening of the Sky Bridge, international passengers will be ferried to their gates by bus. Some parts of the TTS’s infrastructure will remain intact, but no longer run trains. London Stansted will acquire ghost stations. The area around London will have one rail system less.

Do People Movers Always Make Sense in an Airport?

As a rail enthusiast, I find I need to sometimes ask myself to take a step back and think critically as to whether a railway is always the best choice for a given situation. The circumstance where there’s talk of removing an existing railway is always difficult to process without a knee-jerk reaction. My mind naturally goes to Beeching and the damage done by virtue of not only closing railway lines, but ensuring many of them couldn’t be easily reopened in the future.

And so we find ourselves in a similar situation at Stansted. In order for the airport to be expanded to cope with expected future levels of passengers, the TTS must go.

And more-so, the parts of the TTS infrastructure which are not needed to physically support existing structures will be built over or demolished, precluding opportunity to reinstate the system in the future. For a transit enthusiast that’s a sad thing to witness, especially for a unique system like this one.

But here’s the thing: The systems in place when an airport originally opened don’t always make sense several decades down the road. What was a convenient way of separating passengers into discrete “packets” to be transited through an airport might not be best when the numbers increase and a continuous flow of passengers becomes more desirable. Travellers may also prefer to have more agency over their movements through the airport, choosing to make their way to their gate in their own time rather than being made to queue for a train, only to be squeezed in with a large number of other passengers.

Anyone who’s travelled through Heathrow’s Terminal 2, aka: “The Queen’s Terminal”, will no doubt realise it’s a very long walk underground from the gates to the main terminal. But the inclusion of escalators and travelators works perfectly well to move the large numbers of people moving through the terminal. For the subset of passengers with limited mobility, lifts and a fleet of electric carts are available on request.

At some airports, a people mover will always make sense. For example, Gatwick’s North and South terminal are far too distant from one another for walking to ever be feasible. But at Stansted, the three satellite terminals are visible across the apron from the departure lounge, and two are even already connected by an air bridge.

Sadly one arrives at the conclusion the circuitous route of the TTS seems somewhat unnecessary given the close proximities and the need to expand the airport. And at the end of 2026 it will be time to bid a fond farewell to one of England’s most unique pieces of transit infrastructure: The Stansted Airport Tracked Transit System.

London Reconnections would like to give special thanks to Emma Cardinal-Sirois for sharing photos of the Stansted TTS and allowing them to be used in this article.

This article was first published on the author’s Heliomass.com site.